Fig 1: Kalachakra sand mandala, Rikon, Switzerland, 1985 (photo Colin Butler)

Fig 1: Kalachakra sand mandala, Rikon, Switzerland, 1985 (photo Colin Butler)

BODHI’s beginnings: India, Nepal and India again

I (Colin) first met Susan almost four years before we co-founded BODHI, that is, in 1985. We were each staying briefly in a guesthouse called Tushita, established in New Delhi by the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition. Westerners could there find some cultural familiarity, a refuge between the dusty buses, slow trains and India’s many dharma attractions. We were each on our first visit to South Asia. Susan was on pilgrimage with some of Geshe Gyeltsen’s students, including Dr Marty Rubin (later a founding director of BODHI America) and Ruth Grant, then a spry retired teacher, in her 80s. (Ruth, in her bequest, was to be become our most generous individual donor). The group Susan was part of had already been to India and Nepal and most, by the time we met, had returned to the US. However, Susan and her friend Neville had instead decided to stay in India, for a little more exploring. In India a highlight for the group had been a visit to Mundgod, a Tibetan refugee settlement south of Mumbai, where Geshe Gyeltsen’s monastery in exile was based. They had also been to other holy places, mostly in Bihar, but also Dharamsala, where the Dalai Lama had been based, with the Tibetan government in exile, since after his dramatic flight from Tibet in 1959.

We met at the time of Deepawali (also called Diwali), the festival of light, celebrated over five days each Indian fall. Like Susan, I had also reached Delhi from Nepal; by then I had been in Asia for a month, during a year’s leave of absence before my final year of medical school in Australia, a self-funded trip to try to work out if I had sufficient interest for a career trying to improve health in what was then generally called the Third World.

By 1985 I had been a Buddhist for almost a decade, and the bodhisattva ideal had impelled me to study medicine. In those pre-internet days, I was then unaware of any Buddhist health charity for whom I could volunteer, to explore my idea of actualising bodhicitta via improving health in a poor country. I had approached the Edward Hillary Trust, based in Nepal, without success. Even though that was not Buddhist, I knew that most of the target population, Sherpas, were.

Instead, I had first volunteered (for 3 months) with two Christian missions in Nigeria, then, as now, Africa’s most populous nation. These were the Sudan Interior Mission and the Sudan United Mission. After Nigeria I spent six months in Europe, studying family medicine, sight-seeing, and completing two short courses in tropical medicine and public health. I also attended the Kalachakra teachings, given for the first time in Europe, by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, in Switzerland. From Europe I had arranged to fly via Delhi to Nepal, where I was to spend two months with the Britain Nepal Medical Trust (BNMT), in the Himalayan foothills in eastern Nepal. Before starting that, I planned to go trekking, towards Muktinath, across the rainshadow in an area of northern Nepal that is culturally and geographically similar to Tibet. I originally had no plans to visit India, other than a few hours at the Delhi airport.

But I reached Nepal a day later than intended, after missing my connecting flight in Delhi, due to inexperience. When I finally reached the Kathmandu terminal a strange thing happened. Perhaps waiting for my backpack to appear in the luggage, a Tibetan, who I did not know, approached me, asking me, in English, if I was Swiss. “No” I said, “but I was recently there", explaining I had been in Rikon, for teachings by the Dalai Lama. After a few more sentences, he said “you must meet my cousin, Rinchen Dharlo - he is the Dalai Lama’s representative for Nepal”. I thanked Mr Dharlo for his card, and told him that when I got back from my trek I would go to see him.

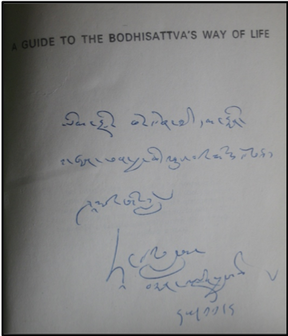

Kathmandu to Dharamsala

Two weeks later I returned to Kathmandu, learning, initially to my distress, that the Britain Nepal Medical Trust wanted me to defer my start by two weeks. Mr Dharlo had better news; he recommended that I meet Mrs Kesang Takla, at that time the secretary of the Department of Health of the Tibetan government in exile, based in Dharamsala. My budget was tight, but I decided to go. Rinchen gave me a letter of introduction to Mrs Takla, written in Tibetan. I discovered that, at the Bank of America in Delhi, I could use my credit card for a cash advance, and I was able to book a flight to Delhi, using the same credit card. Back in Delhi, I stayed overnight in Tushita, where I saw a photograph of Kalu Rinpoche to which I was very attracted. I was told that he lived near Darjeeling, and I instantly decided that I wanted to go there on the way back to Kathmandu. Probably the next day, I found the bank, withdrew US$200, and set off for Dharamsala. I got the cheapest bus possible; it seemed to take 5 hours simply to get out of Delhi, as it kept on stopping to collect freight. About 14 uncomfortable hours later I finally arrived in McLeod Gang, probably by taxi from the Dharamsala bus station. Soon after, I walked slightly down hill, to the central Tibetan Administration, near to Delek Hospital. Seeing Mrs Takla proved fast and easy, and she suggested that I try to meet the Dalai Lama. Although I had, at that stage, never met His Holiness, I had seen him twice, both during his first visit to Australia (1982) and then in Rikon, for over a week, as one of over 6,000 people in an enormous tent. I had taken the teachings very seriously, and, when it was over, had twice lined up (each time for hours) to glimpse the incredible sand mandala, the first time I had ever seen such an expression of devotion and insight (see figure 1).

I (Colin) first met Susan almost four years before we co-founded BODHI, that is, in 1985. We were each staying briefly in a guesthouse called Tushita, established in New Delhi by the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition. Westerners could there find some cultural familiarity, a refuge between the dusty buses, slow trains and India’s many dharma attractions. We were each on our first visit to South Asia. Susan was on pilgrimage with some of Geshe Gyeltsen’s students, including Dr Marty Rubin (later a founding director of BODHI America) and Ruth Grant, then a spry retired teacher, in her 80s. (Ruth, in her bequest, was to be become our most generous individual donor). The group Susan was part of had already been to India and Nepal and most, by the time we met, had returned to the US. However, Susan and her friend Neville had instead decided to stay in India, for a little more exploring. In India a highlight for the group had been a visit to Mundgod, a Tibetan refugee settlement south of Mumbai, where Geshe Gyeltsen’s monastery in exile was based. They had also been to other holy places, mostly in Bihar, but also Dharamsala, where the Dalai Lama had been based, with the Tibetan government in exile, since after his dramatic flight from Tibet in 1959.

We met at the time of Deepawali (also called Diwali), the festival of light, celebrated over five days each Indian fall. Like Susan, I had also reached Delhi from Nepal; by then I had been in Asia for a month, during a year’s leave of absence before my final year of medical school in Australia, a self-funded trip to try to work out if I had sufficient interest for a career trying to improve health in what was then generally called the Third World.

By 1985 I had been a Buddhist for almost a decade, and the bodhisattva ideal had impelled me to study medicine. In those pre-internet days, I was then unaware of any Buddhist health charity for whom I could volunteer, to explore my idea of actualising bodhicitta via improving health in a poor country. I had approached the Edward Hillary Trust, based in Nepal, without success. Even though that was not Buddhist, I knew that most of the target population, Sherpas, were.

Instead, I had first volunteered (for 3 months) with two Christian missions in Nigeria, then, as now, Africa’s most populous nation. These were the Sudan Interior Mission and the Sudan United Mission. After Nigeria I spent six months in Europe, studying family medicine, sight-seeing, and completing two short courses in tropical medicine and public health. I also attended the Kalachakra teachings, given for the first time in Europe, by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, in Switzerland. From Europe I had arranged to fly via Delhi to Nepal, where I was to spend two months with the Britain Nepal Medical Trust (BNMT), in the Himalayan foothills in eastern Nepal. Before starting that, I planned to go trekking, towards Muktinath, across the rainshadow in an area of northern Nepal that is culturally and geographically similar to Tibet. I originally had no plans to visit India, other than a few hours at the Delhi airport.

But I reached Nepal a day later than intended, after missing my connecting flight in Delhi, due to inexperience. When I finally reached the Kathmandu terminal a strange thing happened. Perhaps waiting for my backpack to appear in the luggage, a Tibetan, who I did not know, approached me, asking me, in English, if I was Swiss. “No” I said, “but I was recently there", explaining I had been in Rikon, for teachings by the Dalai Lama. After a few more sentences, he said “you must meet my cousin, Rinchen Dharlo - he is the Dalai Lama’s representative for Nepal”. I thanked Mr Dharlo for his card, and told him that when I got back from my trek I would go to see him.

Kathmandu to Dharamsala

Two weeks later I returned to Kathmandu, learning, initially to my distress, that the Britain Nepal Medical Trust wanted me to defer my start by two weeks. Mr Dharlo had better news; he recommended that I meet Mrs Kesang Takla, at that time the secretary of the Department of Health of the Tibetan government in exile, based in Dharamsala. My budget was tight, but I decided to go. Rinchen gave me a letter of introduction to Mrs Takla, written in Tibetan. I discovered that, at the Bank of America in Delhi, I could use my credit card for a cash advance, and I was able to book a flight to Delhi, using the same credit card. Back in Delhi, I stayed overnight in Tushita, where I saw a photograph of Kalu Rinpoche to which I was very attracted. I was told that he lived near Darjeeling, and I instantly decided that I wanted to go there on the way back to Kathmandu. Probably the next day, I found the bank, withdrew US$200, and set off for Dharamsala. I got the cheapest bus possible; it seemed to take 5 hours simply to get out of Delhi, as it kept on stopping to collect freight. About 14 uncomfortable hours later I finally arrived in McLeod Gang, probably by taxi from the Dharamsala bus station. Soon after, I walked slightly down hill, to the central Tibetan Administration, near to Delek Hospital. Seeing Mrs Takla proved fast and easy, and she suggested that I try to meet the Dalai Lama. Although I had, at that stage, never met His Holiness, I had seen him twice, both during his first visit to Australia (1982) and then in Rikon, for over a week, as one of over 6,000 people in an enormous tent. I had taken the teachings very seriously, and, when it was over, had twice lined up (each time for hours) to glimpse the incredible sand mandala, the first time I had ever seen such an expression of devotion and insight (see figure 1).

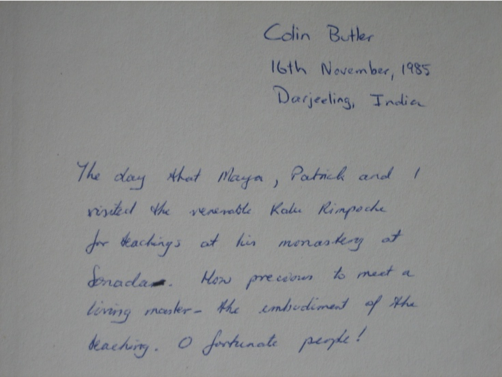

Fig. 2. Inscription written by His Holiness XIVth Dalai Lama, in Shantideva's book "A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life"

Fig. 2. Inscription written by His Holiness XIVth Dalai Lama, in Shantideva's book "A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life"

Two days after meeting Mrs Takla, I had a personal meeting with His Holiness and his secretary, in his quarters just down the hill from McLeod Ganj, towards Kashmir Cottage. I don’t have a photo, but I do have the book he gave me; it has something written to me in Tibetan, but I’m unsure if it’s dated (see figure 2). His Holiness encouraged me to persist with my medical studies. I imagine quite a few readers will have encountered the Dalai Lama; if you have, you will know how wonderful it is.

Soon after I was back in Delhi, but only for one or two nights, as I still wanted to go to Darjeeling, to search for Kalu Rinpoche. It was there, and then, at Tushita, that I met Susan and Neville, who in 2019 published her book The Master on the Mountain. Susan and I exchanged addresses, but she later told me that she didn’t keep mine for long.

I then left by train for Siliguri, the gateway for Darjeeling in the Himalayan foothills. The long journey started in the evening. As it did, every wall I could see was lit by thousands of candles, with no electric lights, in honour of Diwali. It was an incredibly moving expression of faith, as well as personally encouraging.

After two nights on the train, travelling alone, sleeping flat on one of the three tiers available in second class (luxury unimaginable on night trains in Australia) and a third night stretched out in a railway waiting room at Siliguri, after arriving at about 2 a.m., I awoke to glimpses of snowy peaks.

Soon after I was back in Delhi, but only for one or two nights, as I still wanted to go to Darjeeling, to search for Kalu Rinpoche. It was there, and then, at Tushita, that I met Susan and Neville, who in 2019 published her book The Master on the Mountain. Susan and I exchanged addresses, but she later told me that she didn’t keep mine for long.

I then left by train for Siliguri, the gateway for Darjeeling in the Himalayan foothills. The long journey started in the evening. As it did, every wall I could see was lit by thousands of candles, with no electric lights, in honour of Diwali. It was an incredibly moving expression of faith, as well as personally encouraging.

After two nights on the train, travelling alone, sleeping flat on one of the three tiers available in second class (luxury unimaginable on night trains in Australia) and a third night stretched out in a railway waiting room at Siliguri, after arriving at about 2 a.m., I awoke to glimpses of snowy peaks.

"On the peak of the white snow mountain in the East

A white cloud seems to be rising towards the sky.

At the instance of beholding it, I remember my teacher

And, pondering over his kindness, faith stirs in me"

(Song of the Eastern Snow Mountain, quoted in Lama Govinda’s “The Way of the White Clouds”)

A white cloud seems to be rising towards the sky.

At the instance of beholding it, I remember my teacher

And, pondering over his kindness, faith stirs in me"

(Song of the Eastern Snow Mountain, quoted in Lama Govinda’s “The Way of the White Clouds”)

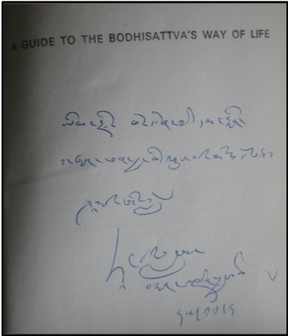

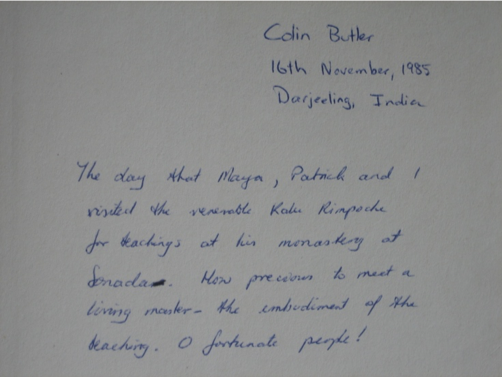

Fig. 3. Inscription in my copy of Sangharakshita’s book "The Thousand Petalled Lotus".

Fig. 3. Inscription in my copy of Sangharakshita’s book "The Thousand Petalled Lotus".

On the bus to Darjeeling I made friends with Patrick, from France. Later, sipping Darjeeling tea in a teahouse, I spoke to him of my hope of meeting Kalu Rinpoche. A woman called Maya overheard us; she told us she was a student of Rinpoche, and that he saw westerners one day a week – the next day, the Saturday. All I had to go was catch the bus to Sonada, slightly back towards the plains, a few stops past Ghoom monastery, vividly described by Lama Govinda in his book The Way of the White Clouds. That day, I also bought The Thousand Petalled Lotus (see figure 3). I did not then know that its author, Sangharakshita, was probably at the time living about 30 miles to the east, across the Teesta valley, in Kalimpong, nor that he and some of his students were to prove so important for BODHI decades later.

Kalu Rinpoche spoke mainly about his experience of long retreats in Tibet. I remember a small, intimate space, with a few monks and a handful of Europeans. There was a brightly colored songbird imprisoned in a small cage. Nothing special seemed to happen, other that I felt in awe. I was glad I had had the chance to see him; dazzled and encouraged by how easy it had been.

Soon after I boarded another overnight bus, this time for the long journey to Kathmandu. The windscreen was broken by a stone early in the journey and it became very cold. The driver wrapped himself in a blanket. After a day or so in Kathamandu I re-crossed most of eastern Nepal again, reaching dusty Biratnagar, on the terai, the Nepali plain, where the BNMT was based. From Biratnagar, I spent a couple of weeks in a series of small villages, in places called Dharan, Dhankuta, Phidin and Tumlingtar. In 1985 these settlements were only accessible by foot, or in the case of Tumlingtar, by a short flight. Each of these centers had a tuberculosis clinic, run by the BNMT and staffed by foreign doctors, each of whom was engaged on a two year contract. My time with the BNMT involved a great deal of strenuous, hilly walking; I remember being almost continuously hungry, as the main food was white rice, dhal and a kind of spinach. One night I stayed in a small hotel, owned by a retired Gurka soldier. He offered me some fat – no meat, only fat. It was obviously a sign of courtesy, however, hungry as I was, I found it difficult to enjoy.

Two of the BNMT doctors were Americans who had trained in the Caribbean; Dan Rikleen and Kristen Lobo. More than 15 years later, they volunteered for BODHI to spend a year in the Doeguling Tibetan Resettlement (DTR) Hospital, in Mundgod, South India. The report that they wrote helped BODHI Australia finally gain its tax-deductible status in 2002.

Sikkim

In January 1988, by then commencing my second year as a qualified doctor, I returned to India, with an Australian friend from medical school, Dr Helena Miksevicius. In 1987 I had written to Tai Situ Rinpoche, one of the four “seat holders” for the Karmapa, the head of the Kagyu lineage (and at that time between recognised reincarnations). I wanted to explore setting up a clinic at or near the Karmapa’s monastery, Rumtek. After some time, I received an invitation from the secretary, encouraging us to visit. Rumtek is to the south east of five peaked Mount Kanchenjunga, on the opposite side of that incredible mountain, where I had spent most of my time in Nepal.

My short visit to Darjeeling in 1985 had made a far deeper impression than my ten weeks in Nepal. Back in Australia I remained fascinated with the mysterious territory to Darjeeling’s north (jammed between Nepal and Bhutan, Sikkim at that time had been incorporated into India for only 13 years). My companion, like me, was interested in Buddhism, and had previously been to India, where she had studied for some months at Benaras Hindu University, in one of India’s most holy cities, Varanasi.

We applied for permission to enter Sikkim many months in advance, but (though we had received a visa for India) the permit had not been granted when we flew from Singapore to Calcutta (now Kolkata). In Calcutta we were told to try for a permit at the Writers Building, the interior of which suggested a permanent battleground between harassed clerks and towers of paper, in those pre-computerised times in India. No one could give us a permit for Sikkim, but someone helpfully suggested that we might try for one in Darjeeling.

After more journeys by train and bus we reached Darjeeling. The official who issued the needed permit was extremely friendly and helpful. Instead of the three days we had applied for from Australia, he offered us seven. Elated, we boarded another bus, and headed east, then north along the Teesta River, into Sikkim. We felt very happy. We reached Gangtok in the late afternoon and checked into the Hotel Tibet. We found out that the bus for Rumtek monastery left at about 5 pm the next day. We passed that day exploring the market place in Gangtok. We also had a short meeting with very friendly people in a hospital, and told them that we wanted to see them again after visiting Rumtek.

Kalu Rinpoche spoke mainly about his experience of long retreats in Tibet. I remember a small, intimate space, with a few monks and a handful of Europeans. There was a brightly colored songbird imprisoned in a small cage. Nothing special seemed to happen, other that I felt in awe. I was glad I had had the chance to see him; dazzled and encouraged by how easy it had been.

Soon after I boarded another overnight bus, this time for the long journey to Kathmandu. The windscreen was broken by a stone early in the journey and it became very cold. The driver wrapped himself in a blanket. After a day or so in Kathamandu I re-crossed most of eastern Nepal again, reaching dusty Biratnagar, on the terai, the Nepali plain, where the BNMT was based. From Biratnagar, I spent a couple of weeks in a series of small villages, in places called Dharan, Dhankuta, Phidin and Tumlingtar. In 1985 these settlements were only accessible by foot, or in the case of Tumlingtar, by a short flight. Each of these centers had a tuberculosis clinic, run by the BNMT and staffed by foreign doctors, each of whom was engaged on a two year contract. My time with the BNMT involved a great deal of strenuous, hilly walking; I remember being almost continuously hungry, as the main food was white rice, dhal and a kind of spinach. One night I stayed in a small hotel, owned by a retired Gurka soldier. He offered me some fat – no meat, only fat. It was obviously a sign of courtesy, however, hungry as I was, I found it difficult to enjoy.

Two of the BNMT doctors were Americans who had trained in the Caribbean; Dan Rikleen and Kristen Lobo. More than 15 years later, they volunteered for BODHI to spend a year in the Doeguling Tibetan Resettlement (DTR) Hospital, in Mundgod, South India. The report that they wrote helped BODHI Australia finally gain its tax-deductible status in 2002.

Sikkim

In January 1988, by then commencing my second year as a qualified doctor, I returned to India, with an Australian friend from medical school, Dr Helena Miksevicius. In 1987 I had written to Tai Situ Rinpoche, one of the four “seat holders” for the Karmapa, the head of the Kagyu lineage (and at that time between recognised reincarnations). I wanted to explore setting up a clinic at or near the Karmapa’s monastery, Rumtek. After some time, I received an invitation from the secretary, encouraging us to visit. Rumtek is to the south east of five peaked Mount Kanchenjunga, on the opposite side of that incredible mountain, where I had spent most of my time in Nepal.

My short visit to Darjeeling in 1985 had made a far deeper impression than my ten weeks in Nepal. Back in Australia I remained fascinated with the mysterious territory to Darjeeling’s north (jammed between Nepal and Bhutan, Sikkim at that time had been incorporated into India for only 13 years). My companion, like me, was interested in Buddhism, and had previously been to India, where she had studied for some months at Benaras Hindu University, in one of India’s most holy cities, Varanasi.

We applied for permission to enter Sikkim many months in advance, but (though we had received a visa for India) the permit had not been granted when we flew from Singapore to Calcutta (now Kolkata). In Calcutta we were told to try for a permit at the Writers Building, the interior of which suggested a permanent battleground between harassed clerks and towers of paper, in those pre-computerised times in India. No one could give us a permit for Sikkim, but someone helpfully suggested that we might try for one in Darjeeling.

After more journeys by train and bus we reached Darjeeling. The official who issued the needed permit was extremely friendly and helpful. Instead of the three days we had applied for from Australia, he offered us seven. Elated, we boarded another bus, and headed east, then north along the Teesta River, into Sikkim. We felt very happy. We reached Gangtok in the late afternoon and checked into the Hotel Tibet. We found out that the bus for Rumtek monastery left at about 5 pm the next day. We passed that day exploring the market place in Gangtok. We also had a short meeting with very friendly people in a hospital, and told them that we wanted to see them again after visiting Rumtek.

Figure 4. Students in Mundgod, India, including from the blind school (supported by Geshe Gyeltsen and his students), present khatas in honor of Geshe Gyeltsen, whose body was brought from Los Angeles for cremation in 2009.

Figure 4. Students in Mundgod, India, including from the blind school (supported by Geshe Gyeltsen and his students), present khatas in honor of Geshe Gyeltsen, whose body was brought from Los Angeles for cremation in 2009.

The impermanence of happiness

The bus to Rumtek left slightly early; my companion was already aboard, but somehow I managed to wave to the driver to stop. We were the only Europeans aboard. As we approached Rumtek young monks in Tibetan Buddhist robes filled the bus. I started to feel joyful. When we reached Rumtek it was dark, but we were expected, we were fed. But after about an hour there I had the most powerful premonition of my life, to that point. Happiness was replaced by apprehension, though I initially could not see why. Perhaps 30 seconds later, four Sikkimese police entered the hall. They had come to escort us, immediately, back to Gangtok. Though not threatening, they insisted; we had no choice. They gave no explanation, and displaying our visa and permit was useless. Our hosts at Rumtek were also helpless.

From the police jeep, the lights of Gangtok sparkled from across the valley; but it was insufficient compensation. Though not arrested we had to report to the police on the following morning. It was my 33rd birthday. The police told us we had to leave Sikkim that same day, by helicopter as they said there was rebel activity near the West Bengal border. Waiting at the tiny airfield we watched the governor of Sikkim board the helicopter. The police, by then quite friendly, said that was auspicious and that one day we would return to Sikkim.

Rather than head south, we first flew to western Sikkim, which at that time was completely off limits to Westerners. We glimpsed the golden roof of Pemayangtse monastery. But the dream of ever helping set up a clinic in Sikkim seemed over.

Later, in Delhi, we wasted a day trying to find out why we had been expelled from Sikkim. We could only conclude that the clerk in Darjeeling had erred, that he should never have issued our permits, and that authorities in Delhi were suspicious of do-gooding doctors. We had never sought to disguise our true purpose from the authorities, but this transparency did not seem to help.

Reconnecting with Susan

A year later, back in Australia, I found and opened the pocket address book of people I had met while travelling in 1985, three years earlier. I had filed people by their nationality, but by the time I met Susan the page for “U” was full. Instead, I had included her name with the Canadians, with a new section in the “C” page marked for California. By 1988 I had completely forgotten that, and discovering her name was a surprise; somehow it seemed significant. I wrote to Susan, to her exotic-seeming address in North Hollywood. To my surprise, two typed airletters soon arrived in response. (Susan was a freelance writer). Our correspondence increased, and in early 1989 I accepted her invitation to stay with her and Ruth Grant, during the Kalachakra teachings, to be given by the Dalai Lama in Los Angeles, for the second time in the U.S. It was to be my first visit to America.

Bodhicitta and emptiness

During the Kalachakra teachings in Santa Monica (Los Angeles) I told Susan of my idea of an affiliation of doctors and others with a sincere interest in the dharma who could collaborate to improve health in places such as India. My time in Nigeria had shown me that Christians could be compassionate and altruistic, but as a Buddhist I had felt out of place. The BNMT staff were secular; the primary motive of the doctors I met seemed to be a sense of adventure; again I did not really fit in.

Apart from to my companion on that trip to Sikkim I don’t think I had then mentioned the idea of a Buddhist influenced aid group to anyone. At that time in Australia, being Buddhist was rare; most doctors I knew seemed either Christian or atheist, and (apart from the Dean of my medical school and a couple of students who had, like me, done electives in the Third World), there seemed little interest in alleviating diseases of poverty in low-income countries.

To my delight, Susan not only liked the idea, but thought we should co-found an organisation. Geshe Gyeltsen, who later supported a school for blind students in Mundgod (see figure 4) was also supportive.

For Susan, the aspiration of bodhicitta was real, as it was for me. When I was a small child one of my favourite stories was about Robin Hood, who famously took from the rich to give to the poor. I had liked it so much that, aged 8, I filled 3 exercise books, 96 pages in total, with my own version of the champion of social justice based in Sherwood forest. In 1965, at a quiz night on a week long camp for several hundred schoolchildren, we had been asked the capital of Tibet. I was the only one who seemed to know, oddly, it seemed to me that I could not recall ever not knowing that. In about the same year, I remember asking my friend Peter (the smartest boy I knew) why he thought that anything existed. Not trees, dogs, or stars, but the potential for a universe. Today, for me, the question remains unanswered, and almost all my life I have strongly felt that the physicists’ explanations for existence (be it the big bang or a steady state universe) misses the main point – why should there be anything? Explanations by materialists such as Richard Dawkins are even more unsatisfactory.

In 1971 I spent my grandmother’s 16th birthday present ($2) at Dymocks Bookshop, in downtown Sydney, eventually buying Alan Watts’ book "The Way of Zen". At Central Sydney Station, going home, I had initiated conversation with a friendly seeming man on the bench next to me. Because he had a backpack, I asked him if he was going on a journey. He saw my book, and said “I’m only going to Greenacre (a suburb); I think you’re going on the journey”. He gave me another book: “The Way of Action” by Christmas Humphreys. He taught me my first mantra, Na Mu Amida Butsu (I take refuge in Amida Buddha). His friendliness made a greater impression than either book.

In mid-1974 I drove (with four friends and a baby) my Volkswagen beetle, from Sydney, almost 2,000 miles north to Cairns, the most northerly city on Australia’s east coast. It was a journey of youthful discovery, camping on beaches, and discovering exotic foods such as avocados and mangoes. But I also heard of two Tibetan lamas teaching in Queensland, and I met my first yogi, a New Zealander who said his name was Omna. On the way south (having left our two friends and their baby in Cairns) we travelled for two days with a hitch-hiker who claimed he was carrying the entire collection of Lobsang Rampa’s books. While impressed by Omna, I was less so with Lobsang Rampa.

In December 1974 I moved south, to a commune, off the grid, called Illusion Farm (now called Dorje Ling), on the Australian island state Tasmania. Its spiritual influence was mainly Hindu. It was set up by Sandy McCutcheon, then working for a local radio station as a disc jockey, and Julie, his then partner. Sandy had travelled extensively, but Julie was even younger than I was, and I was only 19. At the time I was the commune’s sole long-staying visitor.

There wasn’t any obvious Buddhist influence, but I was attracted to the idea of maya, of illusion, the dance of mental and physical phenomena. Mostly, that first year at Illusion Farm was a period of hard work, mahjong during the winter rain, cold nights in either a large tent or an old wooden house, a lot of science fiction reading (and a bit about the Sufi teacher Nasrudin), organic gardening, butter churning, draft horses and constructing a mud brick hut. (It proved much warmer than the house.) In my second year there, soon after my 21st birthday, I saw an advertisement for a meditation course, to be given in a Catholic monastery near Melbourne. The ad did not mention Buddhism, but I registered anyway. It turned out to be a short course based on the Lam Rim, given over 10 days by Yeshe Khadro, an Australian nun who had been taught by Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa in Kopan, near Kathmandu. These were the same Tibetan lamas that I had heard of in Queensland in 1974. Many years later, I learned that the seminal western philosopher, David Hume, whose work I chiefly encountered when studying theories of causation in epidemiology, may have been influenced by the Lam Rim, via the Jesuit Ippolito Desideri who had travelled to Lhasa in 1716, had mastered Tibetan, and had written an Italian translation of the Lam Rim (see figure 5).

The bus to Rumtek left slightly early; my companion was already aboard, but somehow I managed to wave to the driver to stop. We were the only Europeans aboard. As we approached Rumtek young monks in Tibetan Buddhist robes filled the bus. I started to feel joyful. When we reached Rumtek it was dark, but we were expected, we were fed. But after about an hour there I had the most powerful premonition of my life, to that point. Happiness was replaced by apprehension, though I initially could not see why. Perhaps 30 seconds later, four Sikkimese police entered the hall. They had come to escort us, immediately, back to Gangtok. Though not threatening, they insisted; we had no choice. They gave no explanation, and displaying our visa and permit was useless. Our hosts at Rumtek were also helpless.

From the police jeep, the lights of Gangtok sparkled from across the valley; but it was insufficient compensation. Though not arrested we had to report to the police on the following morning. It was my 33rd birthday. The police told us we had to leave Sikkim that same day, by helicopter as they said there was rebel activity near the West Bengal border. Waiting at the tiny airfield we watched the governor of Sikkim board the helicopter. The police, by then quite friendly, said that was auspicious and that one day we would return to Sikkim.

Rather than head south, we first flew to western Sikkim, which at that time was completely off limits to Westerners. We glimpsed the golden roof of Pemayangtse monastery. But the dream of ever helping set up a clinic in Sikkim seemed over.

Later, in Delhi, we wasted a day trying to find out why we had been expelled from Sikkim. We could only conclude that the clerk in Darjeeling had erred, that he should never have issued our permits, and that authorities in Delhi were suspicious of do-gooding doctors. We had never sought to disguise our true purpose from the authorities, but this transparency did not seem to help.

Reconnecting with Susan

A year later, back in Australia, I found and opened the pocket address book of people I had met while travelling in 1985, three years earlier. I had filed people by their nationality, but by the time I met Susan the page for “U” was full. Instead, I had included her name with the Canadians, with a new section in the “C” page marked for California. By 1988 I had completely forgotten that, and discovering her name was a surprise; somehow it seemed significant. I wrote to Susan, to her exotic-seeming address in North Hollywood. To my surprise, two typed airletters soon arrived in response. (Susan was a freelance writer). Our correspondence increased, and in early 1989 I accepted her invitation to stay with her and Ruth Grant, during the Kalachakra teachings, to be given by the Dalai Lama in Los Angeles, for the second time in the U.S. It was to be my first visit to America.

Bodhicitta and emptiness

During the Kalachakra teachings in Santa Monica (Los Angeles) I told Susan of my idea of an affiliation of doctors and others with a sincere interest in the dharma who could collaborate to improve health in places such as India. My time in Nigeria had shown me that Christians could be compassionate and altruistic, but as a Buddhist I had felt out of place. The BNMT staff were secular; the primary motive of the doctors I met seemed to be a sense of adventure; again I did not really fit in.

Apart from to my companion on that trip to Sikkim I don’t think I had then mentioned the idea of a Buddhist influenced aid group to anyone. At that time in Australia, being Buddhist was rare; most doctors I knew seemed either Christian or atheist, and (apart from the Dean of my medical school and a couple of students who had, like me, done electives in the Third World), there seemed little interest in alleviating diseases of poverty in low-income countries.

To my delight, Susan not only liked the idea, but thought we should co-found an organisation. Geshe Gyeltsen, who later supported a school for blind students in Mundgod (see figure 4) was also supportive.

For Susan, the aspiration of bodhicitta was real, as it was for me. When I was a small child one of my favourite stories was about Robin Hood, who famously took from the rich to give to the poor. I had liked it so much that, aged 8, I filled 3 exercise books, 96 pages in total, with my own version of the champion of social justice based in Sherwood forest. In 1965, at a quiz night on a week long camp for several hundred schoolchildren, we had been asked the capital of Tibet. I was the only one who seemed to know, oddly, it seemed to me that I could not recall ever not knowing that. In about the same year, I remember asking my friend Peter (the smartest boy I knew) why he thought that anything existed. Not trees, dogs, or stars, but the potential for a universe. Today, for me, the question remains unanswered, and almost all my life I have strongly felt that the physicists’ explanations for existence (be it the big bang or a steady state universe) misses the main point – why should there be anything? Explanations by materialists such as Richard Dawkins are even more unsatisfactory.

In 1971 I spent my grandmother’s 16th birthday present ($2) at Dymocks Bookshop, in downtown Sydney, eventually buying Alan Watts’ book "The Way of Zen". At Central Sydney Station, going home, I had initiated conversation with a friendly seeming man on the bench next to me. Because he had a backpack, I asked him if he was going on a journey. He saw my book, and said “I’m only going to Greenacre (a suburb); I think you’re going on the journey”. He gave me another book: “The Way of Action” by Christmas Humphreys. He taught me my first mantra, Na Mu Amida Butsu (I take refuge in Amida Buddha). His friendliness made a greater impression than either book.

In mid-1974 I drove (with four friends and a baby) my Volkswagen beetle, from Sydney, almost 2,000 miles north to Cairns, the most northerly city on Australia’s east coast. It was a journey of youthful discovery, camping on beaches, and discovering exotic foods such as avocados and mangoes. But I also heard of two Tibetan lamas teaching in Queensland, and I met my first yogi, a New Zealander who said his name was Omna. On the way south (having left our two friends and their baby in Cairns) we travelled for two days with a hitch-hiker who claimed he was carrying the entire collection of Lobsang Rampa’s books. While impressed by Omna, I was less so with Lobsang Rampa.

In December 1974 I moved south, to a commune, off the grid, called Illusion Farm (now called Dorje Ling), on the Australian island state Tasmania. Its spiritual influence was mainly Hindu. It was set up by Sandy McCutcheon, then working for a local radio station as a disc jockey, and Julie, his then partner. Sandy had travelled extensively, but Julie was even younger than I was, and I was only 19. At the time I was the commune’s sole long-staying visitor.

There wasn’t any obvious Buddhist influence, but I was attracted to the idea of maya, of illusion, the dance of mental and physical phenomena. Mostly, that first year at Illusion Farm was a period of hard work, mahjong during the winter rain, cold nights in either a large tent or an old wooden house, a lot of science fiction reading (and a bit about the Sufi teacher Nasrudin), organic gardening, butter churning, draft horses and constructing a mud brick hut. (It proved much warmer than the house.) In my second year there, soon after my 21st birthday, I saw an advertisement for a meditation course, to be given in a Catholic monastery near Melbourne. The ad did not mention Buddhism, but I registered anyway. It turned out to be a short course based on the Lam Rim, given over 10 days by Yeshe Khadro, an Australian nun who had been taught by Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa in Kopan, near Kathmandu. These were the same Tibetan lamas that I had heard of in Queensland in 1974. Many years later, I learned that the seminal western philosopher, David Hume, whose work I chiefly encountered when studying theories of causation in epidemiology, may have been influenced by the Lam Rim, via the Jesuit Ippolito Desideri who had travelled to Lhasa in 1716, had mastered Tibetan, and had written an Italian translation of the Lam Rim (see figure 5).

Figure 5. David Hume in 1766; portrait by Alan Ramsay. “When I enter most intimately into what I call myself,” Hume wrote “I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe anything but the perception.”

Figure 6. His Holiness the His Holiness XIVth Dalai Lama, Susan Woldenberg and Colin Butler, Dharamsala, India, 1990. Photo: Tenzin Geshe Tethong

Figure 6. His Holiness the His Holiness XIVth Dalai Lama, Susan Woldenberg and Colin Butler, Dharamsala, India, 1990. Photo: Tenzin Geshe Tethong

Hearing the Lam Rim was like unwrapping layers of understanding that I had temporarily forgotten; each new layer made utter sense, although some aspects seemed placed there more for marketing purposes than to be taken literally (such as comparing a precious human rebirth to accidentally putting one’s nose through a golden ring, floating in the ocean). As a result, I determined that I would also like to meet the lamas, who were to arrive in the winter. Soon after, I hitch-hiked to Chenrezig Institute, Queensland (having long ago sold my car; I had very little income at the commune), and, with about 250 others, I attended a longer, three week version of the Lam Rim, this time taught in Tibetan by Lama Yeshe, and hesitantly translated into English by Lama Zopa. At its end, particularly impressed by the Tong Len practice (a method to cultivate compassion) I almost ordained as a Gelugpa monk; instead I decided to try to enrol in medical school, even if this meant foregoing life at Illusion Farm.

Fast forward 13 years

Thirteen years later, soon after my second Kalachakra initiation, I returned to Sydney from Los Angeles. Restlessness generally trumps sustained, meditative concentration for me, but, almost the day I arrived, while sitting cross legged and trying to focus on my breath, the words “Benevolent Organisation for Development, Health and Insight” came into my mind, with its acronym, BODHI. I wrote to Susan, who, soon after, decided to cross the Pacific to join me, landing at the tiny airport of Wynyard, Tasmania, near where I was then working as a locum family doctor. Soon after, we wrote to His Holiness the Dalai Lama to ask if he would be one of BODHI’s patrons; we also invited Thich Nhat Hahn, Jimmy Carter, James Lovelock, the Aga Khan and Prince Charles. Of these, only His Holiness replied in the affirmative; his letter reached us on Friday December 29, 1989 – the last mailing day of the decade; we took that as auspicious.

In early 1990 Susan and I each left Tasmania. I flew to London to study for a diploma in tropical medicine and hygiene (public health); Susan returned to her home to Los Angeles. Later that year we met again, this time in India. First, we went to Dharamsala, where Susan and I had a 20 minute meeting with His Holiness in which we discussed our dreams and hopes for BODHI (see figure 6).

During this meeting we mentioned how some Christian monks and nuns served in the community, such as nurses and social workers. When we said this, the Dalai Lama clapped his hands, saying “excellent excellent”. But two years later, when Susan and I were again in Dharamsala, we asked, via the senior monks at Namgyal monastery, if any of the junior monks wanted to volunteer for training as health workers; they did not.

Still in 1990, assisted by Dr Kathy Holloway, who I had met in London while studying tropical medicine, we visited at least six Tibetan refugee camps, including three in the southern state of Karnataka (Mundgod, Kollegal and Bylakuppe), one in the eastern state of Orissa (Bhandara) and two in Himachal Pradesh. We gathered ideas, and tried to work out how BODHI, with its slender resources, could best help the Tibetans. That visit to India (by then my fifth, Susan’s third) lasted two months; following it Susan returned to America, I went back to Tasmania. We did not know it, but ill-health was to allow Susan only one more visit to India, in 1992-93. I, however, have been there another ten times (as of time of publication of these memories, December 2019).

Susan, while living separately to me in Los Angeles in 1991, was helped by two of Geshe Gyeltsen’s most devoted students, Jean and Fran Paone, to successfully apply for 501(c)3 status for BODHI. We found two more co-directors, each from California; Dr Marty Rubin and Scott Trimingham. Marty (as earlier mentioned) had been to India with Susan and Geshe Gyeltsen in 1985; Scott was an old friend of Susan's, and an environmental activist. In 1991 we also produced our first newsletter, which we called BODHI Times. We posted copies, each of a single sheet of paper folded to create four pages, to hundreds of people, using names that we obtained mostly from Geshe Gyeltsen’s center. The Dalai Lama also sent us some names, one of whom, the Swiss industrialist Baron von Thyssen-Bornemisza, later gave us US$1,000 for six consecutive bi-annual newsletters.

Susan and I were finding our trans-Pacific relationship increasingly difficult, and we decided to get married. Later in 1991 Geshe Gyeltsen performed our wedding ceremony, in Tarzana, in the San Fernando valley, not far from where Susan went to high school. We then returned to Australia, where we slowly established BODHI Australia as a legal entity. Dr Damien Morgan was, briefly, a director, followed by Dr Denis Wright, an academic who supervised Susan’s degree in Asian Studies at the University of New England, Australia. Denis was a specialist on Bangladesh. He remained a director until his premature death in 2013.

Our first project: BOWSER (see also BODHI Times 4 – 1993)

From Australia, in late 1992, we left for another long visit to India, including to try to implement BODHI’s first project, which we called BOWSER (BODHI’s Wild Dog Sterilisation and Eradication of Rabies Program). At this time I was supporting Susan and I by doing locums in general practice (family medicine). That gave us the flexibility to travel; but the cost of the travel and the time away from paid work kept us feeling financially stretched. We did not use donors’ funds (which at that stage were very scarce) for travel.

When we had visited Tibetan refugee camps in 1990, a recurrent complaint concerned wild dogs. The Tibetans occasionally fed these dogs, rewarding them just enough to keep them hanging around. Naturally, Tibetans didn’t like to kill them, though in one location, we were told, when a visit from the Dalai Lama was imminent, the dogs were pacified with the sedative diazepam (hidden in food) and trucked miles away. They soon came back. We also heard of rare cases of rabies in Tibetans.

We gradually developed a programme to try to sterilise some of these dogs, using a method developed by Professor Talwar, at the National Institute of Immunology, based in New Delhi, and with whom we had corresponded. Prof Talwar described his invention as a vaccine. In early 1993 we were back in Dharmasala, together with Jeremy and Christine Townend, two Australians who had formed Help in Suffering, an animal refuge then mainly operating in Jaipur, Rajastan. The National Institute of Immunology also generously sent a scientist to Dharamsala, to help teach the vaccination technique.

Unfortunately, our wild dog program was an almost complete failure, though we gained valuable experience. We had originally thought the vaccine could be given fairly easily into muscle, provoking an immune reaction which would somehow cause sterility. I had never heard of this before, and was sceptical, but we felt we had to try. (Even now, it is not possible to do this, though wild dog population control programs are possible, involving surgical sterilisation, now as then. Help in Suffering was asked in 1993 by the World Society for the Protection of Animals to test the Guidelines for Dog Population Management).

The injection that we wanted to try proved not to be a true vaccine, but instead simply an adjuvant; something often given in vaccines to increase the effectiveness of the antigen (e.g. part of a virus at a very low dose), the true vaccine. Even worse, the injection required considerable skill to administer, by precise administration into each epididymis, tubes that run from each testicle. If given in the right spot, the injection could provoke an inflammatory reaction, which might in some cases lead to sufficient scarring of the epididymis to trigger sterility. Importantly, such a method was not the same as castration. In theory that would be a benefit, as infertile male dogs would still have all their hormones, and still try to defend their territory. If it had worked it should have led to fewer puppies being born. Although, we always recognised that a single fertile male dog, slipping through the injection net, could easily lead to puppies!

Before we realised the impossibility of these hurdles, we searched for a Tibetan who we hoped to train, initially in Jaipur (supervised by Help in Suffering), as a kind of para-vet. Eventually, we found a Ladhaki, who had once served in the Indian army. He seemed to have the requisite courage, but I discovered that it was virtually impossible to teach him to draw fluid into a syringe to inject a practice orange, at least in 30 minutes. But we sent him to Jaipur nevertheless. Alas, he didn’t stay long, returning home during Losar, Tibetan New Year. We also gradually realised that any work involving animals had very low status for Tibetans. We had to abandon this project, though elements of it persist, not only in Help in Suffering’s work, but also Vets without Borders.

Tenpa TK and Dawa Dhondup (see also BODHI Times 9 – 1995)

From Dharmsala, we retraced much of the route of our earlier visit, travelling to Karnataka, focussing on Mundgod (near Hubli) and Kollegal, several hours from Mysore. Unlike in 1990, we did not have the required permits, even though we had applied. In each of these camps we met people with whom we formed bonds, which in one case lasted until his death.

In Mundgod, we were befriended by Tenpa TK, who was a pharmacist who helped administer the DTR Hospital (mentioned above). Tenpa, born in western Tibet, had contracted polio soon after escaping with his family to India in 1962. He had been hospitalised in India for over two years; partly as a result he was an enthusiastic health promoter.

“Ever since the day I remember that I can do any serious thinking, I have wanted to be of some help to my people, especially those who are poor, sick and ignorant.” Tenpa TK

Tenpa became BODHI’s first representative in India (for a tiny salary). His story is here. Unfortunately, he died in about 2004; I last saw him (and his wife), in the nearest large town to Mundgod, in Hubli, in 1997. That brief visit to India (my 6th) was especially difficult. I was returning to Australia (and Susan) after almost a year in London, where I had studied for my higher degree in epidemiology. I not only lacked a permit to visit Mundgod, but barely had a visa, due, again, to overly suspicious Indian officials, and an excess of transparency on my part. Although I primarily wanted to visit India to speak at and attend a conference to celebrate the centenary of the discovery that malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes, made in Hyderabad in 1897, I had also told the Indian officials of my plan to go to Mundgod.

Returning to 1992, from Mundgod, Susan and I had headed via Hubli to Bangalore (now Bengaluru), the state capital of Karnataka. The train line was under repair, so we caught another bus. The most striking feature of that journey was slowly passing a huge human caravan, consisting of what seemed like hundreds of horse-drawn carriages, each piled high with possessions, lit by hand carried lamps.

From Bangalore we went to Mysore and then, eventually, by three-wheeler (for over an hour), to the remote Tibetan camp in Kollegal, then near a herd of over 40 elephants that sometimes raided the Tibetans’ maize fields. Lacking a permit, we were anxious to avoid detection. I spent a long and dispiriting day seeing Tibetans with tuberculosis, many of whom had drug resistant strains, which required toxic and expensive medication of dubious efficacy. It underlined, to me, the value of public health (prevention) and also the great difficulty of prevention. Some of the patients who best understood the importance of taking their medication were seriously ill; they had learned from their previous mistakes (i.e. by not properly taking their medication with sufficient perseverance) but by then their deeper understanding and assiduous compliance was not able to bring them much benefit.

In Kollegal we were heartened to meet a qualified science teacher called Dawa Dhondup, who had foregone his own career, to the consternation of his family, to set up a coaching school, which gave the isolated school students a slightly better chance at education. He called this school TEACH. Supporting Dawa, in 1993, we facilitated the placement of two Australian volunteers to Kollegal for several months, a nurse called Wendy and her adult son, Kim (at their own expense and risk). A letter from Wendy can be read here. She and Kim seemed very useful, but she (appropriately) criticises a poorly trained nurse’s aide, who was re-using syringes and needles, which is likely to have spread infections, including Hepatitis B (common in India and among Tibetans), and perhaps even worse infections.

The International Network of Engaged Buddhists

In 1994 Susan and I went to a meeting near Bangkok, Thailand, organised by The International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB). There, we met this organization’s founder, Sulak Sivaraksa, and several others who have since acted, either formally or informally, as advisors for BODHI, including Alan Senauke, from San Francisco, and Christopher Queen, from Harvard. I later attended two other INEB meetings; one in Nagpur, India (2005) and the other at a small nunnery near Taipei, Taiwan, in 2007. In 2011 an INEB meeting was held in Bodh Gaya. We did not attend, but paid the expenses for one of our partners in India to go (Susanta Chakma) and our representative at the time, Krishan Chakma.

The Revolving Sheep Bank in Tibet (see also BODHI Times 19, published in 2000)

When we met the Dalai Lama in 1990 he had recommended BODHI work in Tibet, but for some years we didn't see how this could be possible. However, it transpired.

In about 1995 two educators, Professor Kim McQuaid and Dr John Gore, from Lake Erie College, in Painesville Ohio, wrote to us, asking if we could help place post graduate students with the Tibetan government in exile, in Dharamsala. In exchange, the students would get course credit. The college (or perhaps the students) would bear the costs and the risk. We did this, but the feedback from the Tibetans was neutral, and we decided not to repeat this trial. However, in 1996, en route to the UK, where I had enrolled to study epidemiology, we visited Kim. This led to the suggestion that we meet Professor Melvyn C Goldstein (and his partner Dr Cynthia Beale), who worked nearby at Case Western University.

By then we had known of Goldstein’s work for many years, not only as editor of the definitive Tibetan English dictionary, but also for his work with Tibetan nomads and Tibetan history. He was regarded with slight concern by some of the Tibetans in exile, as he maintained a sufficiently good relationship with the Chinese authorities to frequently visit Tibet. However, we always felt that Mel was on the Tibetans’ side.

Gradually, our relationship developed. Through Mel, we first provided funds for school materials in Tibet. In 1999, he asked us for funds for the “Revolving Sheep Bank, after being knocked back by better established aid organisations, including the American Red Cross (see figure 7). This was a micro credit scheme that ingeniously did not involve interest, as borrowers repay the bank in kind. The nomads kept all by-products (cheese, wool, etc), repaying their loan in years four and five.

The budget - US$10,000 a year for each of five years – looked forbidding, but, very sadly, our old friend Ruth Grant passed away at about that time, leaving BODHI just enough to fund the sheep bank’s first year. Following that, Marty Rubin did some determined fund raising among his medical colleagues in the Napa Valley of California; this was featured in newsletter 23. After 5 years the Bridge Fund, based in San Francisco, took over ongoing funding of the Revolving Sheep Bank. By 2009, the Revolving Sheep Bank had succeeded beyond our wildest dreams. It has become the prototype of yak banks started by other Western NGOs in Tibet. Nomads from the far west of Tibet have also approached Prof Goldstein for advice about starting sheep banks in their areas.

Other work relevant to Tibet

BODHI has not funded anything in Tibet since the Revolving Sheep Bank; it is extremely difficult for an NGO our size. However, we have not been completely silent on human rights issues in Tibet, though more as an individual than an NGO, particularly in response to the crisis of self-immolation by Tibetans (which I believe is futile). In 2012 I submitted an abstract for a a conference linking health and ecology, held in Kunming, China. Unsurprisingly, this abstract was censored, scored as zero out of five. It led to a book chapter (short version here) and an article in the Tibetan Review.

Figure 8. One of about 8 schools I visited with Suresh Bauddha and Susanta Chakma, near Mainpuri, India over 2 days in 2009. Teachers from this and other schools had not formal trainers as teachers, but were sent by BODHI for some in depth training in Kolkata at the Barefoor teacher centre, organised by Loreto convent. Photo: Colin Butler

Figure 8. One of about 8 schools I visited with Suresh Bauddha and Susanta Chakma, near Mainpuri, India over 2 days in 2009. Teachers from this and other schools had not formal trainers as teachers, but were sent by BODHI for some in depth training in Kolkata at the Barefoor teacher centre, organised by Loreto convent. Photo: Colin Butler

Barefoot teachers (newsletter 40, published in 2011)

One project that we were particularly pleased with was training village teachers from remote parts of Uttar Pradesh, in partnership with the Loreto Convent and sister Cyril Mooney in Kolkata and their programme for barefoot teachers. This was in conjunction with the Youth Buddhist Society, (YBS) and its founder, Suresh Bauddha. However, the lack of FCRA status for YBS makes this very hard to extend (see figure 8).

Sister Mooney (see Figure 9, below) wrote: "We have rarely had such a good and cooperative group. Everyone seemed to take to the training like ducks to water. They have had training as far as Class I ... If they come back to us we could do Class II, Ill and IV and then a little later on the senior school level. We would be very happy to have them back as they were so eager to learn and so ready to take in whatever we could give them."

One project that we were particularly pleased with was training village teachers from remote parts of Uttar Pradesh, in partnership with the Loreto Convent and sister Cyril Mooney in Kolkata and their programme for barefoot teachers. This was in conjunction with the Youth Buddhist Society, (YBS) and its founder, Suresh Bauddha. However, the lack of FCRA status for YBS makes this very hard to extend (see figure 8).

Sister Mooney (see Figure 9, below) wrote: "We have rarely had such a good and cooperative group. Everyone seemed to take to the training like ducks to water. They have had training as far as Class I ... If they come back to us we could do Class II, Ill and IV and then a little later on the senior school level. We would be very happy to have them back as they were so eager to learn and so ready to take in whatever we could give them."

Dalits, Dr Ambedkar and Karunadeepa.

The practice of “untouchability” has existed in India for millennia. So called untouchables face systemic discrimination, especially by the main four higher castes, including the Brahmins (the priestly class). In 1935, untouchables were placed on a list (or schedule) of castes. But, increasingly, this group prefer the name "Dalit" (sometimes translated as "broken"). Of at least 100 million Dalits in India, between 10 and 30 million have converted to Buddhism. Dr BR Ambedkar is the most famous Dalit ever born, to date. In October 1956, after an illustrious career, including as the first Minister of Law and Justice and as chair of the committee which drafted the Indian constitution, Dr Ambedkar spoke to an audience in Nagpur, of several hundred thousand Dalits, who converted to Buddhism, as a result.

In the early 1990s I wrote to Sangharakshita (whose book I had bought in Darjeeling in 1985, see figure 4); in return he sent me two books: the second volume of his autobiography (“Facing Mt Kanchenchunga") and his book about Dr Ambedkar, called “Ambedkar and Buddhism” (the link to the free book has gone but this is a useful resource). Sangharaskshita, then a young Buddhist monk, met Dr Ambedkar three times in the 1950s. One of these meeting helped lead Dr Ambedkar to take the Three Refuges and Five Precepts, from U Chandramani of Kusinara, the most senior Buddhist monk in India.

Describing their last meeting, about a month after the Nagpur conversions, Sangharaskshita wrote:

"But Ambedkar would not hear of our going. Or rather, he would not hear of my going .. there was evidently much that was weighing on his mind, much that he wanted to speak to me about, and he had no intention of allowing bodily weakness and suffering to prevent him from continuing the conversation .. he spoke of his hopes and fears – mostly fears – for the movement of conversion to Buddhism that he had inaugurated. .. I had the distinct impression that he somehow knew we would not be meeting again and that he wanted to transfer to my shoulders some of the weight that he was no longer able to bear himself. There was still so much to be done, the sad, tired voice was saying … so much to be done.…"

Soon after, Sangharakshita caught the overnight train to Nagpur, en route to Calcutta, where he was met on the platform by a crowd of about 2,000 “excited ex-Untouchables”. Less than an hour later, they learned that Dr Ambedkar had died the previous night. Sangharakshita wrote:

"The speakers seemed utterly demoralized. .. the Society’s downtown office was being besieged by thousands of grief-stricken people who, knowing that I had arrived in Nagpur, were demanding that I should come and speak to them. .. I told my visitors to organize a proper condolence meeting for seven o’clock that evening. I would address it and do my best to console people, who from the accounts that now started coming in were frantic with grief and anxiety at the sudden loss of their great leader.

A condolence meeting was held .. it was quite dark and the long columns of mourners were still converging on the place from all directions. They came clad in white – the same white that they had worn for the conversion ceremony only seven weeks earlier – and every man, woman, and child carried a lighted candle, so that the Park was the dark hub of a wheel with a score of golden spokes. .. There was no stage and, apart from a petromax or two, no lighting other than that provided by the thousands of candles. By the time I rose to speak – standing on the seat of a rickshaw –about 100,000 people had assembled. .. I should have been the last speaker but as things turned out I was the first. In fact I was the only speaker. Not that there were not others who wanted to pay tribute to the memory of the departed leader. One by one, some five or six of Ambedkar’s most prominent local supporters attempted to speak, and one by one they were forced to sit down again as, overcome by emotion, they burst into tears after uttering only a few words. Their example proved to be contagious. When I started to speak the whole of the vast gathering was weeping, and sobs and groans rent the air. In the light cast by the petromax I could see grey-haired men in convulsions of grief at my feet.

It would have been strange if I had remained unaffected by the sight of so much anguish and so much despair, and I was indeed deeply moved. But though I felt the tears coming to my eyes .. there was no time to indulge in emotion. Ambedkar’s followers had received a terrible shock. They had been Buddhists for only seven weeks, and now their leader, in whom their trust was total, and on whose guidance in the difficult days ahead they had been relying, had been snatched away. Poor and illiterate as the vast majority of them were, and faced by the unrelenting hostility of the Caste Hindus, they did not know which way to turn and there was a possibility that the whole movement of conversion to Buddhism would come to a halt or even collapse.

At all costs something had to be done. I therefore delivered a vigorous and stirring speech in which, after extolling the greatness of Ambedkar’s achievement, I exhorted my audience to continue the work he had so gloriously begun and bring it to a successful conclusion. ‘Baba Saheb’ was not dead but alive. He lived on in them, and he lived on in them to the extent to which they were faithful to the ideals for which he stood and for which he had, quite literally, sacrificed himself. This speech, which lasted for an hour or more, was not without effect. Ambedkar’s stricken followers began to realize that it was not the end of the world, that there was a future for them even after their beloved ‘Baba Saheb’s’ death, and that the future was not devoid of hope.

While I was speaking I had an extraordinary experience. Above the crowd there hung an enormous Presence. Whether that Presence was Ambedkar’s own departed consciousness still hovering over his followers, or whether it was the collective product of their thoughts at that time of trial and crisis, I do not know, but it was as real to me as the people I was addressing. In the course of the next four days I visited practically all the ex-untouchable ‘localities’ of Nagpur and made more than forty speeches, besides initiating about 30,000 people into Buddhism and delivering lectures at Nagpur University and at the local branch of the Ramakrishna Mission .. there was no doubt that during those five memorable days I had forged a very special link with the Buddhists of Nagpur and, indeed, with all Ambedkar’s followers.

It was a link that was destined to endure. During the decade that followed I spent much of my time with the ex-untouchable Buddhists of Nagpur, Bombay, Poona, Jabalpur, and Ahmedabad, as well as with those who lived in the small towns and the villages of central and western India. I learned to admire their cheerfulness, their friendliness, their intelligence, and their loyalty to the memory of their great emancipator. I also learned to appreciate how terrible were the conditions under which, for so many centuries, they had been compelled to live."

In a modest way, BODHI is part of this work; our current projects in India are exclusively with Dalits, inspired by Dr Ambedkar and also by Sangharakshita and his students. A grandfather of Karunadeepa, who leads one of our current two partner projects, in Pune, attended the conversion ceremony led by Dr Ambedkar in Nagpur. Our other current partner, Aryaketu, lives in Nagpur.

The practice of “untouchability” has existed in India for millennia. So called untouchables face systemic discrimination, especially by the main four higher castes, including the Brahmins (the priestly class). In 1935, untouchables were placed on a list (or schedule) of castes. But, increasingly, this group prefer the name "Dalit" (sometimes translated as "broken"). Of at least 100 million Dalits in India, between 10 and 30 million have converted to Buddhism. Dr BR Ambedkar is the most famous Dalit ever born, to date. In October 1956, after an illustrious career, including as the first Minister of Law and Justice and as chair of the committee which drafted the Indian constitution, Dr Ambedkar spoke to an audience in Nagpur, of several hundred thousand Dalits, who converted to Buddhism, as a result.

In the early 1990s I wrote to Sangharakshita (whose book I had bought in Darjeeling in 1985, see figure 4); in return he sent me two books: the second volume of his autobiography (“Facing Mt Kanchenchunga") and his book about Dr Ambedkar, called “Ambedkar and Buddhism” (the link to the free book has gone but this is a useful resource). Sangharaskshita, then a young Buddhist monk, met Dr Ambedkar three times in the 1950s. One of these meeting helped lead Dr Ambedkar to take the Three Refuges and Five Precepts, from U Chandramani of Kusinara, the most senior Buddhist monk in India.

Describing their last meeting, about a month after the Nagpur conversions, Sangharaskshita wrote:

"But Ambedkar would not hear of our going. Or rather, he would not hear of my going .. there was evidently much that was weighing on his mind, much that he wanted to speak to me about, and he had no intention of allowing bodily weakness and suffering to prevent him from continuing the conversation .. he spoke of his hopes and fears – mostly fears – for the movement of conversion to Buddhism that he had inaugurated. .. I had the distinct impression that he somehow knew we would not be meeting again and that he wanted to transfer to my shoulders some of the weight that he was no longer able to bear himself. There was still so much to be done, the sad, tired voice was saying … so much to be done.…"

Soon after, Sangharakshita caught the overnight train to Nagpur, en route to Calcutta, where he was met on the platform by a crowd of about 2,000 “excited ex-Untouchables”. Less than an hour later, they learned that Dr Ambedkar had died the previous night. Sangharakshita wrote:

"The speakers seemed utterly demoralized. .. the Society’s downtown office was being besieged by thousands of grief-stricken people who, knowing that I had arrived in Nagpur, were demanding that I should come and speak to them. .. I told my visitors to organize a proper condolence meeting for seven o’clock that evening. I would address it and do my best to console people, who from the accounts that now started coming in were frantic with grief and anxiety at the sudden loss of their great leader.

A condolence meeting was held .. it was quite dark and the long columns of mourners were still converging on the place from all directions. They came clad in white – the same white that they had worn for the conversion ceremony only seven weeks earlier – and every man, woman, and child carried a lighted candle, so that the Park was the dark hub of a wheel with a score of golden spokes. .. There was no stage and, apart from a petromax or two, no lighting other than that provided by the thousands of candles. By the time I rose to speak – standing on the seat of a rickshaw –about 100,000 people had assembled. .. I should have been the last speaker but as things turned out I was the first. In fact I was the only speaker. Not that there were not others who wanted to pay tribute to the memory of the departed leader. One by one, some five or six of Ambedkar’s most prominent local supporters attempted to speak, and one by one they were forced to sit down again as, overcome by emotion, they burst into tears after uttering only a few words. Their example proved to be contagious. When I started to speak the whole of the vast gathering was weeping, and sobs and groans rent the air. In the light cast by the petromax I could see grey-haired men in convulsions of grief at my feet.

It would have been strange if I had remained unaffected by the sight of so much anguish and so much despair, and I was indeed deeply moved. But though I felt the tears coming to my eyes .. there was no time to indulge in emotion. Ambedkar’s followers had received a terrible shock. They had been Buddhists for only seven weeks, and now their leader, in whom their trust was total, and on whose guidance in the difficult days ahead they had been relying, had been snatched away. Poor and illiterate as the vast majority of them were, and faced by the unrelenting hostility of the Caste Hindus, they did not know which way to turn and there was a possibility that the whole movement of conversion to Buddhism would come to a halt or even collapse.

At all costs something had to be done. I therefore delivered a vigorous and stirring speech in which, after extolling the greatness of Ambedkar’s achievement, I exhorted my audience to continue the work he had so gloriously begun and bring it to a successful conclusion. ‘Baba Saheb’ was not dead but alive. He lived on in them, and he lived on in them to the extent to which they were faithful to the ideals for which he stood and for which he had, quite literally, sacrificed himself. This speech, which lasted for an hour or more, was not without effect. Ambedkar’s stricken followers began to realize that it was not the end of the world, that there was a future for them even after their beloved ‘Baba Saheb’s’ death, and that the future was not devoid of hope.

While I was speaking I had an extraordinary experience. Above the crowd there hung an enormous Presence. Whether that Presence was Ambedkar’s own departed consciousness still hovering over his followers, or whether it was the collective product of their thoughts at that time of trial and crisis, I do not know, but it was as real to me as the people I was addressing. In the course of the next four days I visited practically all the ex-untouchable ‘localities’ of Nagpur and made more than forty speeches, besides initiating about 30,000 people into Buddhism and delivering lectures at Nagpur University and at the local branch of the Ramakrishna Mission .. there was no doubt that during those five memorable days I had forged a very special link with the Buddhists of Nagpur and, indeed, with all Ambedkar’s followers.

It was a link that was destined to endure. During the decade that followed I spent much of my time with the ex-untouchable Buddhists of Nagpur, Bombay, Poona, Jabalpur, and Ahmedabad, as well as with those who lived in the small towns and the villages of central and western India. I learned to admire their cheerfulness, their friendliness, their intelligence, and their loyalty to the memory of their great emancipator. I also learned to appreciate how terrible were the conditions under which, for so many centuries, they had been compelled to live."

In a modest way, BODHI is part of this work; our current projects in India are exclusively with Dalits, inspired by Dr Ambedkar and also by Sangharakshita and his students. A grandfather of Karunadeepa, who leads one of our current two partner projects, in Pune, attended the conversion ceremony led by Dr Ambedkar in Nagpur. Our other current partner, Aryaketu, lives in Nagpur.

Figure 10. His Holiness the Dalai Lama, teaching mainly to “low-caste” Hindus, in Sankissa, India, 2015. Organised by the Youth Buddhist Society, from Mainpuri (photo Colin Butler)

Figure 10. His Holiness the Dalai Lama, teaching mainly to “low-caste” Hindus, in Sankissa, India, 2015. Organised by the Youth Buddhist Society, from Mainpuri (photo Colin Butler)

The loss of Susan and Denis

In about 2010 Dr Denis Wright was diagnosed with a glioblastoma, an almost inevitably fatal brain tumor. He passed away in December 2013, aged 66. Five months later, Susan, then aged 65, was diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer; she died barely 5 months afterwards; her lifespan thus was almost identical to Denis. Their deaths represented a crisis, not only personally, but for both branches of BODHI. However, I was determined to try to keep BODHI alive, not only as a tribute to Susan, but from a sense of obligation to our partners and beneficiaries, at that time mainly Chakmas in the Changlang district of Arunachal Pradesh and in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. At that time we also used to provide some scholarships for poor Muslim girls, in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

The beginning of recovery

In late 2014 Suresh Baudha (mentioned above in the context of barefoot teachers), the founder of the Youth Buddhist Society invited me, again, to Sankissa, for the first ever teachings there by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, in this most remote pilgrimage site, near Mainpuri in Uttar Pradesh (see figure 10). I travelled with Aryadharma, a Buddhist student of Sangharakshita, who I had recently met in the context of a protest against coal mining in NSW. While at Sankissa I had a brief meeting with His Holiness (February 2015). I told him of Susan’s death, he gave me a big hug, and he seemed to remember me. I was very grateful for this, and pleased that we had gone to the effort.

In 2019, thanks especially to the Lhakpa Tshoko, the representative of the Office of Tibet for Australia and New Zealand, the Dalai Lama wrote a very nice letter congratulating us on our first 30 years (see).

BODHI’s finances

For many years the income BODHI received (combining BODHI US and BODHI Australia) was tiny (A$4,000 per annum, then A$6,000, eventually A$10,000 then A$25,000, peaking at over A$50,000 in 2013, but falling to A$30,000 after Susan’s death. In 2019, income rose to A$36,000. Almost all funds have been from the public, although in 2015 BODHI US received a grant of US$5,000 in Susan’s name.

Reflections on aid