Remembering Vanya Kewley

This essay is based on obituaries in The Independent and the Guardian.

So far, we haven't been able to find excerpts of Kewley's documentaries on the internet, including YouTube and BFI.

"Personal courage and a commitment to exposing human rights abuses were the qualities that made the documentary-maker Vanya Kewley admired and trusted by commissioning editors across British television."

Never was that courage more on display than when she made Tibet: a Case to Answer (1988). Disturbed by claims of genocide, torture, the destruction of monasteries and art treasures, the looting of natural resources and the establishment of a nuclear base, Kewley set out to obtain first-hand accounts. In 1985, she began to establish contacts inside Tibet, and two years later persuaded commissioning editor David Lloyd to fund Channel 4's most expensive documentary to date, for the current affairs series Dispatches.

Vanya travelled in disguise wearing peasant garb (as Alexander David-Neel did seventy years before her), helped by local guides for six weeks while covering more than 4,000 miles across Tibet's mountains and valleys. She interviewed some 160 individuals, including monks, nuns and former political prisoners, who described on camera their experiences of torture, famine and arbitrary imprisonment; some of the women spoke of enforced abortions they had suffered. A former teacher told of the Chinese dividing Tibetans into work units, feeding them starvation diets and beating and torturing many. Until recently, the use of the Tibetan language had been forbidden, and books were burned and monuments destroyed in an attempt to wipe out an entire culture. Four young nuns recalled electric cattle prods being applied all over their naked bodies after they staged a peaceful demonstration calling for Tibetan independence..

She heard stories of torture, mass graves and cultural destruction, and witnessed undersize children. She filmed the nuclear base, with interviewees claiming that babies were being born with deformities and animals dying possibly as the result of a radiation leak; a Chinese doctor revealed that he had been made to perform enforced abortions and sterilisations.

Kewley admitted to emotions ranging from fear to terror over the weeks as she worried about her cover being broken. Occupation forces were never far away. Kewley persuaded a French mountaineer to smuggle most of the film footage out before she left on her own flight.

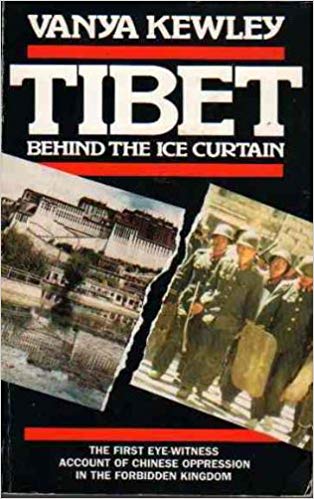

In Lhasa, she found the indigenous population swamped by Chinese – confirming another claim, that Tibetans were now outnumbered in their own land. A former monk who had been jailed and tortured after confronting Chinese tanks talked of prisoners being shot in "batches" and the survivors resorting to eating human flesh to feed themselves. "Seeing the beads of sweat glisten on his forehead, his eyes glaze with pain as he talked, was one of the most traumatic experiences of my career," wrote Kewley in her 1990 book Tibet: Behind the Ice Curtain.

The resulting documentary was broadcast by Channel 4 in 1988, caused a stir worldwide and was, unusually, shown twice more in the UK within a few months.

The film presented detailed Tibetan statistics claiming that more than a million people (out of a population of six million) had died at the hands of the Chinese. The film drew repeated protests from Beijing when it was shown in 17 other countries. China's ambassadors in those posts declined offers to debate the film live on air with its producer-director. Although the documentary was screened for British MPs and US Congress members, Kewley despaired that conditions for Tibetans seemed to worsen and that the world was more interested in trading with China.

The historic trip was the culmination of Kewley's fascination for Tibet, which began as a child in India, where she was born of a French mother and a British diplomat father in Calcutta who shared his deep interest in the region with his daughter. Kewley was educated at convent schools in India, France and Switzerland, and studied philosophy and history at the Sorbonne, in Paris, before moving to London and qualifying as a nurse.

In 1965, she joined Granada Television as a researcher on a regional news programme. Then she became a producer and director on World in Action (1968-71). In 1969, Kewley was captured and beaten by soldiers while making a film about genocide in South Sudan – her first foreign assignment – and took a film crew into the Nigerian Civil War, where a year later, she secured an exclusive interview with the leader of the Biafran forces."

In the mid-1970s she uncovered on film the widespread use of torture in Paraguay (Paradise Lost, 1976), and at different times reported human rights and women's rights controversies from Bangladesh, Chad, Chile, Lebanon, Northern Ireland, Nicaragua, Oman and Russia (in Nagorno Karabakh).

In 1991 she returned to Tibet, this time smuggling herself into the country across the Himalayas, hidden beneath the floorboards of a van, to make a follow-up to the earlier film, again for Channel 4, entitled Voices from Tibet. In this she revealed that martial law still existed despite a Chinese claim that it had been ended.

Danger was never far away in the locations in which she chose to film. Vanya and her crew were severely beaten up by Ugandan border guards in when mistaken for mercenaries, and she was also imprisoned there for a time; she was clubbed unconscious and came close to being raped in South Sudan while filming and living without permission among the country's Ananya "freedom fighters"; in Vietnam she contracted infective hepatitis and liver abscesses while filming in the jungle war zones.

Kewley interviewed the Dalai Lama at his home in Dharamsala for her 1975 film The Lama King and remained a lifelong friend. She last saw him

In 1993, Kewley was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease and gave up documentaries, returning to her first career as a nurse, offering her services in Rwanda and Bosnia."

In 2000 she married Michael Lambert, a soil scientist who died of bone cancer in 2004. As well as sponsoring the education of two girls and a boy – Pema Choezam and Choezam Tsering, from Tibet, and Jean-Paul Habineza in Rwanda – she also adopted them and they survive her.

So far, we haven't been able to find excerpts of Kewley's documentaries on the internet, including YouTube and BFI.

"Personal courage and a commitment to exposing human rights abuses were the qualities that made the documentary-maker Vanya Kewley admired and trusted by commissioning editors across British television."

Never was that courage more on display than when she made Tibet: a Case to Answer (1988). Disturbed by claims of genocide, torture, the destruction of monasteries and art treasures, the looting of natural resources and the establishment of a nuclear base, Kewley set out to obtain first-hand accounts. In 1985, she began to establish contacts inside Tibet, and two years later persuaded commissioning editor David Lloyd to fund Channel 4's most expensive documentary to date, for the current affairs series Dispatches.

Vanya travelled in disguise wearing peasant garb (as Alexander David-Neel did seventy years before her), helped by local guides for six weeks while covering more than 4,000 miles across Tibet's mountains and valleys. She interviewed some 160 individuals, including monks, nuns and former political prisoners, who described on camera their experiences of torture, famine and arbitrary imprisonment; some of the women spoke of enforced abortions they had suffered. A former teacher told of the Chinese dividing Tibetans into work units, feeding them starvation diets and beating and torturing many. Until recently, the use of the Tibetan language had been forbidden, and books were burned and monuments destroyed in an attempt to wipe out an entire culture. Four young nuns recalled electric cattle prods being applied all over their naked bodies after they staged a peaceful demonstration calling for Tibetan independence..

She heard stories of torture, mass graves and cultural destruction, and witnessed undersize children. She filmed the nuclear base, with interviewees claiming that babies were being born with deformities and animals dying possibly as the result of a radiation leak; a Chinese doctor revealed that he had been made to perform enforced abortions and sterilisations.

Kewley admitted to emotions ranging from fear to terror over the weeks as she worried about her cover being broken. Occupation forces were never far away. Kewley persuaded a French mountaineer to smuggle most of the film footage out before she left on her own flight.

In Lhasa, she found the indigenous population swamped by Chinese – confirming another claim, that Tibetans were now outnumbered in their own land. A former monk who had been jailed and tortured after confronting Chinese tanks talked of prisoners being shot in "batches" and the survivors resorting to eating human flesh to feed themselves. "Seeing the beads of sweat glisten on his forehead, his eyes glaze with pain as he talked, was one of the most traumatic experiences of my career," wrote Kewley in her 1990 book Tibet: Behind the Ice Curtain.

The resulting documentary was broadcast by Channel 4 in 1988, caused a stir worldwide and was, unusually, shown twice more in the UK within a few months.

The film presented detailed Tibetan statistics claiming that more than a million people (out of a population of six million) had died at the hands of the Chinese. The film drew repeated protests from Beijing when it was shown in 17 other countries. China's ambassadors in those posts declined offers to debate the film live on air with its producer-director. Although the documentary was screened for British MPs and US Congress members, Kewley despaired that conditions for Tibetans seemed to worsen and that the world was more interested in trading with China.

The historic trip was the culmination of Kewley's fascination for Tibet, which began as a child in India, where she was born of a French mother and a British diplomat father in Calcutta who shared his deep interest in the region with his daughter. Kewley was educated at convent schools in India, France and Switzerland, and studied philosophy and history at the Sorbonne, in Paris, before moving to London and qualifying as a nurse.

In 1965, she joined Granada Television as a researcher on a regional news programme. Then she became a producer and director on World in Action (1968-71). In 1969, Kewley was captured and beaten by soldiers while making a film about genocide in South Sudan – her first foreign assignment – and took a film crew into the Nigerian Civil War, where a year later, she secured an exclusive interview with the leader of the Biafran forces."

In the mid-1970s she uncovered on film the widespread use of torture in Paraguay (Paradise Lost, 1976), and at different times reported human rights and women's rights controversies from Bangladesh, Chad, Chile, Lebanon, Northern Ireland, Nicaragua, Oman and Russia (in Nagorno Karabakh).

In 1991 she returned to Tibet, this time smuggling herself into the country across the Himalayas, hidden beneath the floorboards of a van, to make a follow-up to the earlier film, again for Channel 4, entitled Voices from Tibet. In this she revealed that martial law still existed despite a Chinese claim that it had been ended.

Danger was never far away in the locations in which she chose to film. Vanya and her crew were severely beaten up by Ugandan border guards in when mistaken for mercenaries, and she was also imprisoned there for a time; she was clubbed unconscious and came close to being raped in South Sudan while filming and living without permission among the country's Ananya "freedom fighters"; in Vietnam she contracted infective hepatitis and liver abscesses while filming in the jungle war zones.

Kewley interviewed the Dalai Lama at his home in Dharamsala for her 1975 film The Lama King and remained a lifelong friend. She last saw him

In 1993, Kewley was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease and gave up documentaries, returning to her first career as a nurse, offering her services in Rwanda and Bosnia."

In 2000 she married Michael Lambert, a soil scientist who died of bone cancer in 2004. As well as sponsoring the education of two girls and a boy – Pema Choezam and Choezam Tsering, from Tibet, and Jean-Paul Habineza in Rwanda – she also adopted them and they survive her.