|

|

Engaged Buddhism

Shelley Anderson

Engaged Buddhism seeks to apply Buddhist principles and insights to social issues. This is not a modern concept. Practitioners have tried to address issues such as poverty and social inequality throughout Buddhism’s 2,500 year history. Indeed, the Buddha often spoke about the ill effects of poverty, and challenged entrenched ideas of gender and caste by accepting both women and men, from any caste, in the original sangha. A few centuries later, the Mauryan King Ashoka showed the possibilities of engaged Buddhist political leadership by renouncing armed conflict and devoting state resources to improving health care and fighting poverty.

21st century engaged Buddhism is concerned about much the same issues. Engaged Buddhism today is so varied and multi-leveled that it might be more accurate to speak of engaged Buddhisms. Engaged Buddhism can encompass an individual undergoing training to develop their compassion; a small local group of Buddhists tackling racism or homelessness within their community; or larger activist networks such as the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (founded in 1989 in Thailand) or the AYUS Network of Buddhist Volunteers on International Cooperation (founded in 1993 in Japan), whose members work on a multitude of issues, from climate change to suicide prevention.

Buddhism has always adapted itself to local conditions and needs; engaged Buddhism does the same. Yet much work remains to be done in terms of developing more nuanced definitions, analyses, tools and resources. Thinkers and activists like Joanna Macy, Phra Phaisan Visalo, Rev. angel Kyodo Williams, Sulak Sivaraksa, Joan Halifax and David Loy are pioneers in this area. Their writings are powerful arguments for engaged Buddhism and the need to reconceptualize ideas that have traditionally encouraged passivity in the face of injustice, such as the caste system, and many forms of slavery, once and sometimes still condoned, even by spiritual leaders. Buddhist interpretations of karma have too often been accused of the latter (1).

What are some specific engaged Buddhist projects? What is working well—and what isn’t working? What makes them Buddhist?

One focus of action is, often, homelessness. Buddhists practitioners in Japan, South Africa, the United States, and elsewhere, try to address the needs of this group in their own local communities. They may work as individuals, as Buddhists in South Africa, by regularly offering simple medical help or food; or they may form specific informal groups, such as Buddhists monks who work with homeless people in Tokyo.

Zen Peacemakers

In 1982 Roshi Bernie Glassman started the Greyston Foundation, a network of socially responsible local businesses in Yonkers, New York, with the specific aim of poverty reduction. The businesses include the Greyston Bakery, which hires homeless people off the street under the motto: “We don’t hire people to bake brownies, we bake brownies to hire people.” Yonkers once had the highest per capita of homelessness in the US; since projects like the Bakery, homelessness has been reduced by half, according to Glassman.

Glassman has also, for the last two decades, led retreats in New York City where retreatants meditate together, sleep on the streets and beg for food and money, learning from homeless people about what their life is like.

Such retreats, along with an annual interfaith Auschwitz Bearing Witness, are also part of the training of the activist group Zen Peacemakers, inspired by Roshi Glassman, which currently has a network of 82 formal affiliates in 12 countries.

Zen Peacemakers have three basic tenets, grounded in Zen practice. These tenets are: not knowing, bearing witness to what is there; and responding skillfully to what is encountered. In other words, activists come with an open mind, not with pre-determined solutions or models to the problems of others.

Training is provided for certain aspects of Zen Peacemakers’ work. There is a two-year certified Buddhist Chaplaincy Training Program for work inside prisons, for end of life care, and for environmental ministries. This specific Program is organized by another US-based initiative, the Upaya Zen Centre, founded by Roshi Joan Halifax. Everyone in a leadership position at this Centre has agreed to abide by the Centre’s Ethics Code, a code which has obvious Buddhists underpinnings:

I vow to do no harm

I vow to do good

I vow to save the many beings

The Upaya Center has also instituted a structural process to deal with disagreements, misunderstandings and violations of this ethical code called the Healing, Ethics and Reconciliation Committee.

International Women’s Partnership for Peace and Justice

Such an open and structural approach to dealing with inevitable internal conflict is necessary and important. Traditionally, relationships among Buddhists, especially those between ordained sangha and lay people, have been dealt with hierarchically. Issues of power abuse and disagreements may not have been addressed at all, especially if such issues arose between male clergy and women, whether the women were ordained or lay. Re-envisioning power relationships is also engaged Buddhism.

This is clear in the work of the Thai-based organization the International Women’s Partnership for Peace and Justice (IWP). The IWP offers training to NGOs and individual activists, especially women and LGBTs (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual), throughout Asia and beyond. As an explicitly Buddhist and feminist organization, the IWP incorporates an examination of power dynamics in all its training. This training includes the Women Allies for Social Change, where activists, both Buddhist and non-Buddhist, from the global South and North can interact and learn from each other in an atmosphere of mutual respect. The IWP also provides anti-oppression training, and a certified, year-long Buddhist Education for Social Transformation course. All these trainings aim for both personal transformation and social change.

The IWP operates from several guiding principles. Believing that methodology is as important as the goal itself, IWP’s trainings are highly participatory and involve consultation and shared decision making. The IWP also promotes and celebrates diversity, as this fosters inner peace and outer solidarity.

Understanding structural violence as a root cause of social problems is another key value. IWP trainers understand that “communities and marginalized groups, once aware that the struggles they face are not self-inflicted, or the result of negative karma or fate, are able to see the possibility of change,” say IWP co-founders Ouyporn Khuankaew and Ginger Norwood. They also stress the importance of unlearning internalized patriarchy, including patriarchal teachings in Buddhism, which sustain and enforce ideas of hierarchical leadership and domination. The IWP has worked with nuns from Ladakh, Cambodia and Thailand; with Burmese activists; with leaders from a variety of Non-governmental organizations and with activist from all over the world.

Shelley Anderson

Engaged Buddhism seeks to apply Buddhist principles and insights to social issues. This is not a modern concept. Practitioners have tried to address issues such as poverty and social inequality throughout Buddhism’s 2,500 year history. Indeed, the Buddha often spoke about the ill effects of poverty, and challenged entrenched ideas of gender and caste by accepting both women and men, from any caste, in the original sangha. A few centuries later, the Mauryan King Ashoka showed the possibilities of engaged Buddhist political leadership by renouncing armed conflict and devoting state resources to improving health care and fighting poverty.

21st century engaged Buddhism is concerned about much the same issues. Engaged Buddhism today is so varied and multi-leveled that it might be more accurate to speak of engaged Buddhisms. Engaged Buddhism can encompass an individual undergoing training to develop their compassion; a small local group of Buddhists tackling racism or homelessness within their community; or larger activist networks such as the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (founded in 1989 in Thailand) or the AYUS Network of Buddhist Volunteers on International Cooperation (founded in 1993 in Japan), whose members work on a multitude of issues, from climate change to suicide prevention.

Buddhism has always adapted itself to local conditions and needs; engaged Buddhism does the same. Yet much work remains to be done in terms of developing more nuanced definitions, analyses, tools and resources. Thinkers and activists like Joanna Macy, Phra Phaisan Visalo, Rev. angel Kyodo Williams, Sulak Sivaraksa, Joan Halifax and David Loy are pioneers in this area. Their writings are powerful arguments for engaged Buddhism and the need to reconceptualize ideas that have traditionally encouraged passivity in the face of injustice, such as the caste system, and many forms of slavery, once and sometimes still condoned, even by spiritual leaders. Buddhist interpretations of karma have too often been accused of the latter (1).

What are some specific engaged Buddhist projects? What is working well—and what isn’t working? What makes them Buddhist?

One focus of action is, often, homelessness. Buddhists practitioners in Japan, South Africa, the United States, and elsewhere, try to address the needs of this group in their own local communities. They may work as individuals, as Buddhists in South Africa, by regularly offering simple medical help or food; or they may form specific informal groups, such as Buddhists monks who work with homeless people in Tokyo.

Zen Peacemakers

In 1982 Roshi Bernie Glassman started the Greyston Foundation, a network of socially responsible local businesses in Yonkers, New York, with the specific aim of poverty reduction. The businesses include the Greyston Bakery, which hires homeless people off the street under the motto: “We don’t hire people to bake brownies, we bake brownies to hire people.” Yonkers once had the highest per capita of homelessness in the US; since projects like the Bakery, homelessness has been reduced by half, according to Glassman.

Glassman has also, for the last two decades, led retreats in New York City where retreatants meditate together, sleep on the streets and beg for food and money, learning from homeless people about what their life is like.

Such retreats, along with an annual interfaith Auschwitz Bearing Witness, are also part of the training of the activist group Zen Peacemakers, inspired by Roshi Glassman, which currently has a network of 82 formal affiliates in 12 countries.

Zen Peacemakers have three basic tenets, grounded in Zen practice. These tenets are: not knowing, bearing witness to what is there; and responding skillfully to what is encountered. In other words, activists come with an open mind, not with pre-determined solutions or models to the problems of others.

Training is provided for certain aspects of Zen Peacemakers’ work. There is a two-year certified Buddhist Chaplaincy Training Program for work inside prisons, for end of life care, and for environmental ministries. This specific Program is organized by another US-based initiative, the Upaya Zen Centre, founded by Roshi Joan Halifax. Everyone in a leadership position at this Centre has agreed to abide by the Centre’s Ethics Code, a code which has obvious Buddhists underpinnings:

I vow to do no harm

I vow to do good

I vow to save the many beings

The Upaya Center has also instituted a structural process to deal with disagreements, misunderstandings and violations of this ethical code called the Healing, Ethics and Reconciliation Committee.

International Women’s Partnership for Peace and Justice

Such an open and structural approach to dealing with inevitable internal conflict is necessary and important. Traditionally, relationships among Buddhists, especially those between ordained sangha and lay people, have been dealt with hierarchically. Issues of power abuse and disagreements may not have been addressed at all, especially if such issues arose between male clergy and women, whether the women were ordained or lay. Re-envisioning power relationships is also engaged Buddhism.

This is clear in the work of the Thai-based organization the International Women’s Partnership for Peace and Justice (IWP). The IWP offers training to NGOs and individual activists, especially women and LGBTs (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual), throughout Asia and beyond. As an explicitly Buddhist and feminist organization, the IWP incorporates an examination of power dynamics in all its training. This training includes the Women Allies for Social Change, where activists, both Buddhist and non-Buddhist, from the global South and North can interact and learn from each other in an atmosphere of mutual respect. The IWP also provides anti-oppression training, and a certified, year-long Buddhist Education for Social Transformation course. All these trainings aim for both personal transformation and social change.

The IWP operates from several guiding principles. Believing that methodology is as important as the goal itself, IWP’s trainings are highly participatory and involve consultation and shared decision making. The IWP also promotes and celebrates diversity, as this fosters inner peace and outer solidarity.

Understanding structural violence as a root cause of social problems is another key value. IWP trainers understand that “communities and marginalized groups, once aware that the struggles they face are not self-inflicted, or the result of negative karma or fate, are able to see the possibility of change,” say IWP co-founders Ouyporn Khuankaew and Ginger Norwood. They also stress the importance of unlearning internalized patriarchy, including patriarchal teachings in Buddhism, which sustain and enforce ideas of hierarchical leadership and domination. The IWP has worked with nuns from Ladakh, Cambodia and Thailand; with Burmese activists; with leaders from a variety of Non-governmental organizations and with activist from all over the world.

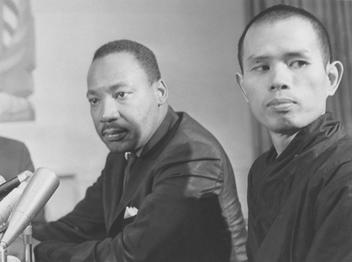

Martin Luther King with Thich Nhat Hahn. Source: http://plumvillage.org/press-releases/thich-nhat-hanh-and-martin-luther-kings-dream-comes-true-in-mississsippi/ permission requested

Martin Luther King with Thich Nhat Hahn. Source: http://plumvillage.org/press-releases/thich-nhat-hanh-and-martin-luther-kings-dream-comes-true-in-mississsippi/ permission requested

The Order of Interbeing

The Order of Interbeing (OI) began in February 1966 when Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh (see left) ordained six lay followers in Vietnam. The six young people, three women and three men, were all leaders in the School of Youth for Social Work (SYSS), a (then) new training program for Vietnamese youth who wanted to work for rural development and social change. The OI was organized explicitly “to bring Buddhism directly into the arena of social concerns’ when the war in Vietnam was escalating” (2). At the core of the Order were 14 Precepts which Order members vowed to study, practice and observe.

From its beginning the Order was conceived as a space for both lay practitioners and monastics. The six original ordained members were given the choice of living as monastics or as lay people. The three women chose to live celibate lives but not to cut their hair. The three men decided to marry and live as lay practitioners.

The 14 Precepts were a reworking of precepts for monks and nuns and specifically of the Bodhisattva Vows. Thich Nhat Hanh felt these 14 precepts encapsulated Buddhist teachings for modern times. Buddhist practitioners will immediately recognize the precepts concerning Right View, Right Speech and Right Livelihood, the emphasis on generosity and on right conduct. There were, however, some very specific refinements.

The third precept, for example, looked at freedom of thought, and encouraged compassionate dialogue as a way to help others renounce fanaticism and narrowness. (Editor’s note: I heard Thich Nhat Hahn give the keynote speech at the UN Day of Vesak conference in Hanoi, Vietnam in 2008 in which he spoke movingly of his work on “deep listening” and success at reducing fanaticism and narrowness). The ninth precept, on truthful and loving speech, stated that OI members should “have the courage to speak out about situations of injustice, even when doing so may threaten your own safety.” And the tenth precept, on protecting the sangha, read

“Do not use the Buddhist community for personal gain or profit, or transform your community into a political party. A religious community, however, should take a clear stand against oppression and injustice and should strive to change the situation without engaging in partisan conflicts".

There are now over 4,200 OI members in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas. It continues to include both lay and monastic practitioners. The original 14 precepts are now called the 14 Mindfulness Trainings. While the core remains the same, the Mindfulness Trainings have been rewritten by Thich Nhat Hanh, in cooperation with Order members, several times. Members commit themselves to at least 60 days of mindfulness a year, to building and practicing within a community of friends, and to regular recitations of the Mindfulness Trainings, which encourage engaged Buddhism.

Environmental Issues

Some OI members have established an Earth Holder Sangha. This is a group of activists who are committed to building sustainable communities and sanghas, and engaging in right action to protect the environment locally, nationally and internationally. They organize days of mindfulness using conference calls and skype. A day of mindfulness for Earth Holders might begin with a guided meditation on keeping fossil fuels in the ground; then a short dharma sharing which looks at the question: “Which of our Plum Village practices help us transform our suffering, engage our compassion, and walk the middle path as we do our best to nurture and preserve our precious planet?” (Editor’s note: Plum Village, based in France, is the main base in the West of the activities led by Thich Nhat Hanh.)

Other OI members are involved in humanitarian work in Vietnam, spearheaded by Sister Chan Khong. Sister Chan Khong was one of the original six OI members. She went into exile with Thich Nhat Hanh and has been a life-long activist. The Vietnam project includes support for orphanages, schools and clinics in rural areas, and supplying emergency relief after natural disasters. Trained as a biologist, Sister Chan Khong also works to raise awareness about environmental degradation inside Vietnam and around the world. Climate change in particular is a major issue for OI members. The Five Contemplations, recited before each meal, have been rewritten to include a vow to help reduce the impact of climate change. Delegations of monastics from Plum Village have participated in the Vatican’s multi-faith initiative to end modern day slavery, and the 2015 United Nations conference on climate change in Paris.

The Order of Interbeing (OI) began in February 1966 when Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh (see left) ordained six lay followers in Vietnam. The six young people, three women and three men, were all leaders in the School of Youth for Social Work (SYSS), a (then) new training program for Vietnamese youth who wanted to work for rural development and social change. The OI was organized explicitly “to bring Buddhism directly into the arena of social concerns’ when the war in Vietnam was escalating” (2). At the core of the Order were 14 Precepts which Order members vowed to study, practice and observe.

From its beginning the Order was conceived as a space for both lay practitioners and monastics. The six original ordained members were given the choice of living as monastics or as lay people. The three women chose to live celibate lives but not to cut their hair. The three men decided to marry and live as lay practitioners.

The 14 Precepts were a reworking of precepts for monks and nuns and specifically of the Bodhisattva Vows. Thich Nhat Hanh felt these 14 precepts encapsulated Buddhist teachings for modern times. Buddhist practitioners will immediately recognize the precepts concerning Right View, Right Speech and Right Livelihood, the emphasis on generosity and on right conduct. There were, however, some very specific refinements.

The third precept, for example, looked at freedom of thought, and encouraged compassionate dialogue as a way to help others renounce fanaticism and narrowness. (Editor’s note: I heard Thich Nhat Hahn give the keynote speech at the UN Day of Vesak conference in Hanoi, Vietnam in 2008 in which he spoke movingly of his work on “deep listening” and success at reducing fanaticism and narrowness). The ninth precept, on truthful and loving speech, stated that OI members should “have the courage to speak out about situations of injustice, even when doing so may threaten your own safety.” And the tenth precept, on protecting the sangha, read

“Do not use the Buddhist community for personal gain or profit, or transform your community into a political party. A religious community, however, should take a clear stand against oppression and injustice and should strive to change the situation without engaging in partisan conflicts".

There are now over 4,200 OI members in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas. It continues to include both lay and monastic practitioners. The original 14 precepts are now called the 14 Mindfulness Trainings. While the core remains the same, the Mindfulness Trainings have been rewritten by Thich Nhat Hanh, in cooperation with Order members, several times. Members commit themselves to at least 60 days of mindfulness a year, to building and practicing within a community of friends, and to regular recitations of the Mindfulness Trainings, which encourage engaged Buddhism.

Environmental Issues

Some OI members have established an Earth Holder Sangha. This is a group of activists who are committed to building sustainable communities and sanghas, and engaging in right action to protect the environment locally, nationally and internationally. They organize days of mindfulness using conference calls and skype. A day of mindfulness for Earth Holders might begin with a guided meditation on keeping fossil fuels in the ground; then a short dharma sharing which looks at the question: “Which of our Plum Village practices help us transform our suffering, engage our compassion, and walk the middle path as we do our best to nurture and preserve our precious planet?” (Editor’s note: Plum Village, based in France, is the main base in the West of the activities led by Thich Nhat Hanh.)

Other OI members are involved in humanitarian work in Vietnam, spearheaded by Sister Chan Khong. Sister Chan Khong was one of the original six OI members. She went into exile with Thich Nhat Hanh and has been a life-long activist. The Vietnam project includes support for orphanages, schools and clinics in rural areas, and supplying emergency relief after natural disasters. Trained as a biologist, Sister Chan Khong also works to raise awareness about environmental degradation inside Vietnam and around the world. Climate change in particular is a major issue for OI members. The Five Contemplations, recited before each meal, have been rewritten to include a vow to help reduce the impact of climate change. Delegations of monastics from Plum Village have participated in the Vatican’s multi-faith initiative to end modern day slavery, and the 2015 United Nations conference on climate change in Paris.

Top left: Liberia (in West Africa) was affected by the Ebola outbreak in 2015-16; bottom right: Many child soldiers in Liberia (now hopefully something in the past) were girls (source: http://europe.newsweek.com/when-liberian-child-soldiers-grow-237780?rm=eu#bigshot/33740); bottom left: A communal latrine charging 10 Liberian dollars per use, above the river in the Fiamah community slum area,

Photograph: Kieran Doherty (Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2012/oct/08/liberia-africa-kieran-doherty-pictures).

Top left: Liberia (in West Africa) was affected by the Ebola outbreak in 2015-16; bottom right: Many child soldiers in Liberia (now hopefully something in the past) were girls (source: http://europe.newsweek.com/when-liberian-child-soldiers-grow-237780?rm=eu#bigshot/33740); bottom left: A communal latrine charging 10 Liberian dollars per use, above the river in the Fiamah community slum area,

Photograph: Kieran Doherty (Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2012/oct/08/liberia-africa-kieran-doherty-pictures).

Peace building: Liberia

Last year (2016) two nuns and two monks went to Liberia from Plum Village. They were invited by the Liberian peace organization the Peace Hut Alliance for Conflict Transformation (PHACT). For several years Liberian peace activists working with PHACT had participated in retreats at Plum Village, learning mindfulness practices to transform both their own and their country’s suffering. PHACT leader Annie Nushann has turned part of her home into a meditation centre and is teaching community women how to use mindfulness in their own peace work. Another PHACT activist, the former military leader Christian Bethelson, is teaching ex-combatants and ex-child soldiers how to use mindfulness to heal Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and to pursue reconciliation. “With the practice of mindfulness you can see them preaching peace and living peace,” he says. Lay OI members are fundraising to help PHACT built traditional peace huts for reconciliation across the country.

Wake Up

Younger OI members are involved in an international movement called Wake Up, whose slogan is “One Buddha is not enough.” They organize meditation classes at universities; discuss issues such as racism and white privilege; and hold meditation flash mobs in train stations. They deepen their practice through retreats both in their own countries and at Plum Village, such as the Wake Up Earth retreat (2016) which addressed the question: “In the current climate crisis and context of wars, how can we balance our deep wish to engage in actions to help the world, with our own personal spiritual journey? How can we find an alternative, healthier, sane, and compassionate lifestyle?”

The international Wake Up Schools movement involves OI members who are students, teachers, educators and school administrators. With the slogan “Happy teachers will change the world”, retreats and days of mindfulness are organized. A training program has been instituted for education professionals in developing their own mindfulness practice and integrating this into school curricula.

Conclusion

How can you deal with the inevitable, frustrating slow pace of social change? How can you deal with the anger at injustice, and not let that anger become destructive? How do make sure your actions are grounded in compassion, not in ego or hate? How can you find the time to practice self-compassion and renew yourself when there is so much urgent work to be done? Anyone who works for social change will find themselves grappling with these issues.

There are a number of lessons to be learned from these experiments in engaged Buddhism. These groups provide training for their members, both in active non-violence and in ways to cultivate inner peace. Such practical training cannot be over-emphasized. It is precisely this training which will help individuals who struggle with such questions.

While the groups given above are clear about their Buddhist roots, they are not evangelical. Activists share their time, energy and resources with people of any religion and of no religion, without propagating Buddhism. The emphasis is on addressing suffering, not on conversion. This non-sectarian approach is an advantage in secular countries and among secular activists, who often reject organized religion as automatically oppressive. It is also help activists heal and refresh themselves and their communities in situations where religion is perceived as a factor in conflict, as among Order of Interbeing projects in Israel and the Occupied Territories.

Another common aspect is the emphasis on community building. Activists in some Zen Peacemakers live together while volunteering on projects, meditating and eating together. Participants in IWP trainings share housing during training and are encouraged to build relationships among themselves in order to sustain them in their often difficult work. OI members are expected to build and practice with a group of like-minded people. Building a community of support often means the difference between staying engaged in a healthy way and dropping out for an activist. Community helps to break the isolation and ostracism many activists experience. A supportive community gives a sense of shared values, understanding and vital feedback to activists. It provides practical support and encouragement when obstacles, like the threat of imprisonment or a sense of despair, arise. Some engaged Buddhist groups provide guidelines (such as the Zen Peacemakers three principles and OI’s 14 Mindfulness Trainings) and explicit practices for dealing with arguments. These hone the community-building skills that activists need to promote collective movements for change.

Some groups also promote self-compassion, in particular the IWP. This is an issue especially for women and girls whose patriarchal upbringing teaches them to give others, not themselves, time and energy. Practices such as meditation and body scans help activists to stop, to not get swept up in emotions like anger, fear or hatred, or in the exciting momentum of a campaign. Self-compassion is important for activists who have been traumatized while struggling to stop violence (3). It can also help activists who meditate together. Examples include Zen Peacemakers members; the meditation, massage and yoga provided for participants by the IWP and the practice of 60 days of mindfulness per year by OI members. These all provide healing and time for renewal and reflection.

There are two issues, however, which need attention. There is nothing explicit within most engaged Buddhist groups about the empowerment of women and girls. Nor is there any policy, training or analysis on gender, except for the pioneering work of the IWP. Such empowerment is often needed in order to counter patriarchal training. The crucial roles women can play in development and peace building have been well documented, and point to the necessity of women’s active involvement in any social change work (4). Scholars and activists with the Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women (which has a recently established branch in Australia) have done much research and documentation about the many roles Buddhist nuns and lay women have played and do play in social change. While there are historically and currently many female role models within both the lay and monastic communities, few organizations explicitly endorse or encourage female leadership. Indeed, more conservative clergy and lay people often oppose and mistrust female leadership at worse, or, at best, see no reason to encourage women to develop themselves and their skills. (Editor’s note: also see, for example, the work of Tenzin Palmo).

It remains to be seen just how far engaged Buddhist activism will go. Sharing and generosity have always been important Buddhist values. Will engaged Buddhism emphasize humanitarian issues to relieve suffering, but without addressing the underlying institutional causes of suffering? Or will it help develop analyses and strategies to confront the status quo and the institutions and systems that lead to the suffering of humans and animals on the planet? The latter, I believe, would support engaged Buddhists from all traditions in their social change work (5).

I end with a quote from Thich Nhat Hanh: “Buddhism means to be awake-mindful of what is happening in one’s body, feelings, mind and in the world. If you are awake you cannot do otherwise than act compassionately to help relieve suffering you see around you. So Buddhism must be engaged in the world. If it is not engaged it is not Buddhism.”

Notes

(1). See Rethinking Karma: The Dharma of Social Justice, edited by Jonathan S. Watts, 2014, International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB).

(2) Chan Khong (Cao Ngoc Phuong), Learning True Love: How I learned & Practiced Social Change in Vietnam. 1993, Parallax Press, Berkeley, page 79.

(3) According to the World Health Organization women are the largest single group of people affected by Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, primarily because of sexual violence. Unipolar depression is twice as common in women as in men. See www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen

(4) The British researcher and writer Cynthia Cockburn has, for example, developed the concept of women’s social courage and social intelligence: “a very special kind of intelligence and courage: The courage to cross the lines drawn between us—which are also lines drawn inside our own heads. And the intelligence to do it safely and productively.” From Where We Stand: War, Women's Activism and Feminist Analysis, Zed Books, London, 2007.

(5) Ken Jones, The New Face of Buddhism: An Alternative Sociopolitical Perspective 2003, Wisdom Publications, Boston, page 179.

About the author: Shelley Anderson (holding placard to left) is a long-time peace activist and a member of the Order of Interbeing.

She has been an advisor to BODHI Australia and BODHI US since 1994, Susan Woldenberg Butler and Colin Butler met her that year at at a conference of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB).

This essay was written in January 2017, slightly edited by Colin Butler and first published in February 2017.

She has been an advisor to BODHI Australia and BODHI US since 1994, Susan Woldenberg Butler and Colin Butler met her that year at at a conference of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB).

This essay was written in January 2017, slightly edited by Colin Butler and first published in February 2017.