|

In June 2019 the 16th Sakyadhita conference will be held, for the first time ever in Australia. See here for details. These are large meetings; the previous one, held in Hong Kong in 2017, attracted about 800 attendees from 31 countries. BODHI Australia will be attending this meeting, represented by at least 4 committee members and one partner, Karunadeepa. Below is the summary of our paper, and below that is our current draft of the full paper (with links that will not be published in the conference proceedings). Posted January 12, 2019; amended February 4. This version is slightly different to the revised one we plan to submit in late February. Authors: Maxine Ross, Karunadeepa, Emilia Della Torre; Colin D. Butler Summary: In 1956 the great reformer Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar led, in Nagpur, India, a mass conversion to Buddhism, involving at least 300,000 people. Millions more have since converted in an ongoing social movement, still keenly needed, reaching for greater justice in India, particularly for women, and particularly for Dalits, once called “untouchables”. Since 2005 the NGO BODHI Australia (founded in 1989) has supported the work of a team led by Karunadeepa, a Dalit whose grandfather took part in the historic Nagpur conversion, and who for decades has worked for an Indian NGO, based in Pune, India, itself largely supported by the UK Karuna Trust, allied with Triratna, whose founder (Venerable Sangharakshita) first met Dr Ambedkar in 1952. The work BODHI Australia has supported with Karunadeepa and her team mainly seeks to enhance the life-chances of slum-dwellers, especially migrants from rural Maharashtra (not necessarily Dalit, nor Buddhist) by improving education, health and awareness of family planning. In 2017 Karunadeepa, with Dalit colleagues, started to develop a new NGO, the Bahujan Hitay Pune Project, entirely governed by Dalit women, which will extend and deepen this work, but which also presents new challenges. In this talk representatives of BODHI Australia will discuss this work. This and other development-promoting projects in India may seem a drop but can also be seen as a key to inspire, to resist oppression, to support development and to assist escape from poverty and vulnerability. Draft (this version is longer than submitted). The paper is designed for reading and some repetition is intended.

Introduction This paper starts by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land this conference is held on, the Gundungurra, the Indigenous people who have thrived on this continent for at least 65,000 years. The authors of this paper are all apprentices of dharma. One of us (Karunadeepa) was born Buddhist. We thank the organisers of this conference for the opportunity to speak and to be published in this setting, alongside the work of people with far more scholarly knowledge of Buddhism than we will ever have. The main goal for this talk and essay is to provide information about the work of some followers (in Pune, India) of Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, who lived in India from 1891 until 1956. Dr Ambedkar was 65 years old when he died, coinciding with the Buddha Jayanti festival, to honour Buddhism’s 2,500th year. The Dalai Lama first arrived in India, mainly to attend this celebration, only a few days before Dr Ambedkar died. While three of us were not born Buddhist, an important reason for our attraction to it is its links with social justice, or fairness, including its rejection of the principle that hereditarily transmitted inequality is legitimate. A basic teaching of many religions (maybe all of them) is the principle of cause and effect. In both Buddhism and Hinduism this principle is called karma, yet the dominant group in each of these two faiths, otherwise quite similar, appears to have a drastically different interpretation of this principle. However, since we do not have time, much less the scholarly qualifications, we cannot trace these differences to early teachings. Instead, the observations in this paper are based mainly on our own personal experience, and our understanding of world events, both today and in the fairly recent past. Whether or not there is a future life, the three authors of this paper, not born Buddhist, have all been, at various times, intensely moved by the unfairness of the social world, as was Dr Ambedkar, born a Hindu, but who converted to Buddhism in October 1956. This was in Nagpur, Maharashtra, in central India, at a mass gathering attended by over 300,000 people, one of whom was a grandfather of the fourth author of this paper, Karunadeepa, the only one of us who was born Buddhist. Inequality In Australia, even among those of European descent, much inequality is passed through the generations, and along family lines, by privilege and unequal access to opportunity. Many people who are wealthy went to exclusive, expensive schools, where, in time, they send their own children. It is well-known, and not just baseless allegation, that many rich people do not pay a fair share of tax. Mackenzie Bezos, the soon to be divorced wife of Jeff Bezos, the founder of the company Amazon, is reported to be due to receive almost US$70 billion in her divorce settlement. In so doing, she will become the richest woman in the world. Bezos, himself, is reported to have humble origins, the son of a teenage mother and a father who has been described as “deadbeat”. But his example of transition from hardship to fabulous wealth is more the exception than the rule. Dr Ambedkar, who served as Law Minister in the first Indian government in 1947, was also exceptional. This was not through extraordinary entrepreneurial skills and alleged “robotization” of employees (the Bezos route), but from an vigorous and courageous intellect, some protection in childhood (due to descent from several generations of soldiers, including his father who rose to be an officer, in an army whose British leaders were far less caste-conscious than most Indians) and hard work. Timing and history were also important. Ambedkar became a leading public figure through his central role in the struggle for Indian independence from Britain, recently reported as plundering the equivalent of $45 trillion from India during its long occupation (1). (For an alternative view, see.) Caste We said that Dr Ambedkar was born Hindu. More accurately, as a member of the Mahar caste, he was born “untouchable”, meaning that close contact with him (even if indirect) was considered, by orthodox Hindus, to pollute or contaminate those who were conditioned, usually since birth, to consider themselves “higher born”, such as Brahmins. For example, as a schoolboy, Ambedkar not only had to sit in a separate section at school (sometimes outside) but could not touch the tap if he was thirsty. In order to drink, a peon, considered “touchable” had to be found to turn it on. Once, while travelling to visit his father, Ambedkar, aged 9, with a brother and two young nephews, all children, were stranded for over an hour at the station (following their first train ride), waiting for a servant that never arrived. The stationmaster was at first sympathetic to four well-dressed children, until he discovered their lowly caste. Eventually, however, he helped them to find, with difficulty, a bullock cart driver, who agreed to take them to their destination, for twice the normal fee. But this was on condition that the children acted as driver while the driver walked, for fear of caste “pollution”. En route (on an overnight journey), as part of a harrowing ordeal, they were refused water (2). Reflecting on this, Ambedkar wrote: “It left an indelible impression .. before this incident occurred, I knew that I was an untouchable, and that untouchables were subjected to certain indignities and discriminations. All this I knew. But this incident gave me a shock such as I had never received before, and it made me think about untouchability--which, before this incident happened, was with me a matter of course, as it is with many touchables as well as the untouchables." To non-Indigenous Australians the idea of caste might seem ludicrous. But there are traces of the caste system here too. We see it in films of past European royalty, and there are echoes in Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers and in the different punishments for white collar (executive) crime compared to those committed by blue collar wearers (working class). Discrimination based on skin colour, religion or age is officially banned (but persists) in Australia, though discrimination based on ability to pay is everywhere. We are nor arguing against laws and punishment, we are instead proclaiming support for the need for a fairer world, including of more equal opportunity. Today, in India, the injustice of caste is milder, especially in urban areas, than in Dr Ambedkar’s time. This is partly due to Dr Ambedkar, partly to increased Westernisation of affluent Indians, and partly the work of liberal Hindus, such as the Ramakrishna mission. But chiefly, it is from the struggle and inspiration of tens of millions of people (sometimes called Dalits) who have renounced the legitimacy of caste as a concept. Karma may still exist, but it no longer can be unquestioningly interpreted as meaning, at least in India, that parental status and income completely determines one’s life course, though, naturally, the culture that children are reared in has a powerful “throwing” effect. Many injustices still exist, in India and elsewhere, including for millions of “tribal” people. One group, seeking to reduce this injustice, and inspired by the teaching and legacy of Dr Ambedkar, is led by Karunadeepa. In 2017, with colleagues, almost all of whom are women, Karunadeepa started to develop a new non-government organization (NGO), called the Bahujan Hitay Pune Project. Since 1982, this work has been undertaken under the umbrella of a larger NGO, the Trailokya Baudha Maha Sangh Gana, but the time has come for a new, legally distinct group. The Bahujan Hitay Pune Project Bahujan refers to the people in the majority, meaning in India, “Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Castes”. Bahujan Hitay roughly translates as “for the welfare of many”. The work of the Bahujan Hitay Pune Project is principally with disadvantaged slum dwellers (scheduled castes and scheduled tribes) in this city of about six million, in the sprawling state of Maharashtra, parts of which are afflicted by drought and accompanying desperation, including farmer suicide. Consequently, many people migrate to Pune, seeking better conditions. This work in Pune has, since 1982, been supported by the Karuna Trust a British charity founded by the late Ven Sangharakshita, who, as young man seeking to work for the good of Buddhism, based mainly in Kalimpong, in the Himalayan foothills, met Dr Ambedkar three times, including shortly before his conversion (3). Since 2005, this work led by Karunadeepa has also been supported by two NGOs with an Australian connection. These NGOs (BODHI and BODHI Australia) were co-founded by Colin Butler and his late wife Susan, in 1989. Since then, these groups have raised and distributed about A$0.5M to partners in six countries in Asia, mostly in India. The acronym means Benevolent Organisation for Development, Health and Insight. BODHI Australia also helps to support the Aryaloka Education Society, a Dalit-led NGO, based in Nagpur, which teaches basic computing skills, mostly to young women from poor villages. Four members of BODHI Australia’s committee (and possibly Karunadeepa) are attending the whole conference, and they hope to learn from and gain inspiration and encouragement from other individuals or NGOs engaged in similar development work. The nature of some of the community work in Pune This work, in the Hadaspar slum, involves education and supplementary feeding for (in 2018) 28 children, all under the age of 5. This is in a very poor community of a group who are mainly Gosavis, who are recent migrants to Pune and live in very disadvantaged circumstances. The children also receive monthly health checks. In addition, meetings are held about 3 times a year involving several of the senior staff (all women) with the parents (mostly mothers) who are encouraged to gain new skills, taught about nutritious foods, given advice about government programmes and also encouraged to practice increased child spacing. (See 2018 report.) The creche helps socialize the young children, improves their education, health and nutrition, and frees the parents’ time so they can earn some money. Other elements of the programme include instruction in hairdressing (in the same room after the children have had lunch and have dispersed.) The children are instructed in devotional songs, but no attempt is made to convert them to Buddhism. Conclusion Whether or not there is a future life, we believe that the creation of good karma is important to try to reduce suffering, in this life. In our understanding of Buddhism, core values are compassion (karuna) and wisdom (panna or prajna), while the first Noble truth refers to the reality of suffering, not only of the perceiver, but also of others – human, animal and even Nature herself. In the three decades of BODHI’s work the barriers facing partner organizations, in order to receive foreign funds have worsened. This steepens the challenge to reach the poorest people and to promote genuinely long-lasting development. But there is still great need. We ask for your support, either directly, or in many other ways. References 1. Patnaik U. How the British impoverished India. Hindustan Times. 2018. 2. Ambedkar BR. Waiting for a visa. In: Moon V, editor. Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches. Bombay, India: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra; 1993. 3. Sangharakshita U. Ambedkar and Buddhism: Windhorse Publications; 1986. Free pdf of book here.

1 Comment

Today, I heard an interview of former U.S. President Barack Obama, by Britain's Prince Harry. Most of it was quite reasonable, but when Obama claimed that we live in the best time ever I could not agree. As I write, the world is experiencing 5 famines, one of which (Yemen) is shaping as the worst in decades. (The other famines are in South Sudan, NE Nigeria, Somalia, and two regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.) Inequality continues to worsen, as do global warming forecasts and climate change reality. 2017 closed with UNICEF reporting how children have been increasingly been used as weapons of war. UNICEF also said parties to conflicts were blatantly disregarding international humanitarian law and children were routinely coming under attack and that rape, forced marriage, abduction and enslavement had become standard tactics in conflicts across Iraq, Syria and Yemen, as well as in Nigeria, South Sudan and Myanmar. This year also saw the ethnic cleansing of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya from Myanmar (see BODHI's statement here) and countless atrocities in many other countries. Australians have also contributed, including via events on Manus Island and Nauru. We have become so conditioned to horror that phenomena such as children or the disabled being forced to act as suicide bombers or entire coral reefs sickening fail to shock us. Surveillance in China has intensified (a reported 480,000 cameras in Beijing, in 2015) with face recognition technology, other forms of artificial intelligence, and a points system to detect resistance are reported as making existence harrowing in Xinjiang. The self-immolations of Tibetans, which I have long argued are a waste of life (given the indifference and false stereotypes of Tibetans most Chinese hold) continue. Chinese state media has allegedly compared the Dalai Lama to Hitler (n.b. link is in Chinese, I cannot tell if it is valid.) According to a recently released report sourced to the British ambassador to China in 1989, the death toll in the Tiananmen square massacre may have exceeded 10,000 people (see box). To this day, the mothers of the murdered students are blocked from visiting graves or holding memorials. Planetary health Professionally, 2017 has been challenging, as I continue to seek academic employment, after resigning from a part-time position as a professor at the University of Canberra in July 2016. In late 2017 I resigned from a pro bono writing role with the United Nations Environment Programme. However I continue with many other writing and academic commitments, also pro bono. I have been invited to a workshop for a book on limits to growth and health, in Canada, in April, 2018. To qualify for permission to enter Canada I need a police check, a legacy of my arrest for civil disobedience in 2014, over climate change. I have so far been waiting for a decision for over 5 weeks. In December 2017, probably the largest ever civil disobedience protest, in the world, by health professionals, against coal mining occurred, with five arrests. I published an article on this in Croakey. There have been successes: three invited talks and 4 publications, two in edited books, three chapters in press (all related to limits to growth and health) and one under review for the BMJ, related to novel entities and the so-called nocebo effect. I have posted 28 essays in my blog Global Change Musings, which had over 15,000 views in 2017. I may be able to enrol for a (second) PhD in 2018, at the University of Sydney, related to "planetary health" and, perhaps, human rights. As we head to 2018, my main frustration is this. Since 1991, including in most of the previous 50 issues of BODHI Times, I have warned of climate change, neoliberalism, root causes of terrorism and poverty traps, especially in Africa and Asia. A great deal that I (and a few others, including Maurice King and the late Tony McMichael) warned of is now occurring. For example, more than 3,000 would-be migrants drowned in 2017, trying to cross the Mediterranean, many of whom were from the Sahel. The arrival of more than 1.5 million desperate people in Europe, in 2017, has contributed to a right-wing backlash, with a neo-Nazi party now sharing power in Austria, and fears of a return to extremism in Germany, including in its military. The world in 2046

BODHI was started by Susan (see below and here for more photos) and I in 1989, almost 28 years ago. If we are lucky, there will still be a semblance of civilisation in 2046, in another 28 years. It is likely to be a world of increased inequality, more famines, more surveillance and less freedom. Artificial intelligence and robots will not lead to utopia, but mass social unrest may be reduced by a universal income, at least in more enlightened locations. Weapons systems may be controlled by algorithms; we will be very lucky to avoid nuclear war. In 1989 this trajectory was broadly foreseeable (see my paper in the 1991 Med J Australia, as an example), but there then seemed time to change it. However, the voices of those trying to head this off have been very faint, and are growing fainter. Neither the dominant media nor dominant academia seems to care; perhaps it is too overwhelming. Despite all this, I continue to believe it is better to light a candle than curse the darkness. BODHI's partners in India and Bangladesh are lighting such candles. Thank you for reading this far and thank you for your support for BODHI's work. "In the forests of Laos and Vietnam, few animals heavier than 80 grams can now be found". (from Stokstad E: The empty forest. Science (2014) 345(6195):396-399.) Limits to growth, planetary boundaries, and planetary health For submission to Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability by Oct 1, 2016 (update December 28, 2017: it was published, though slightly different to this version) Comments welcome! Colin D Butler1,2

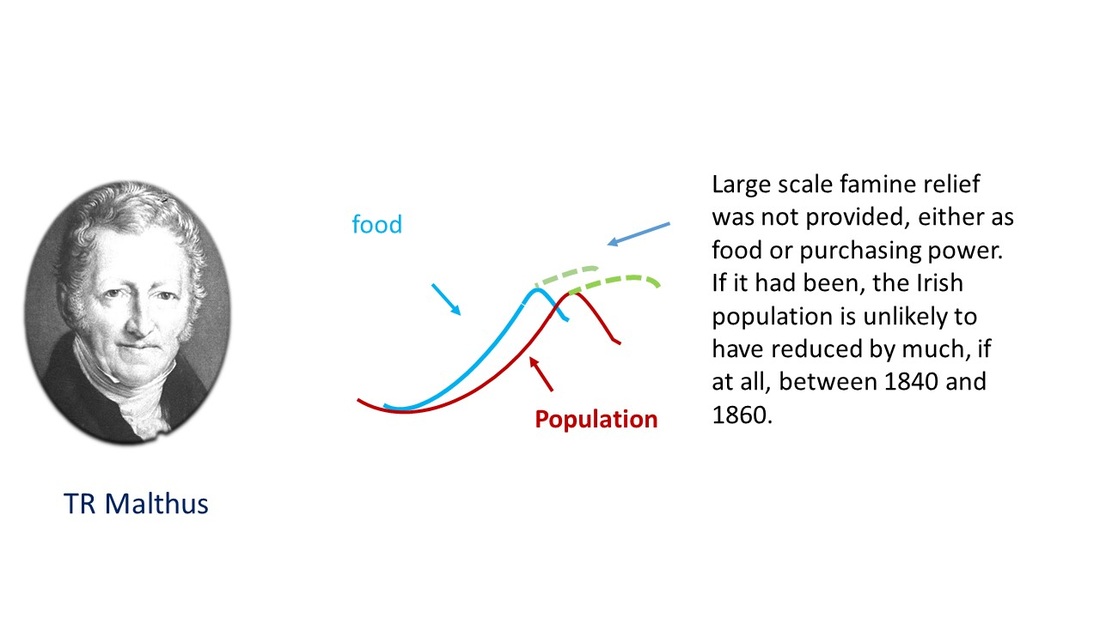

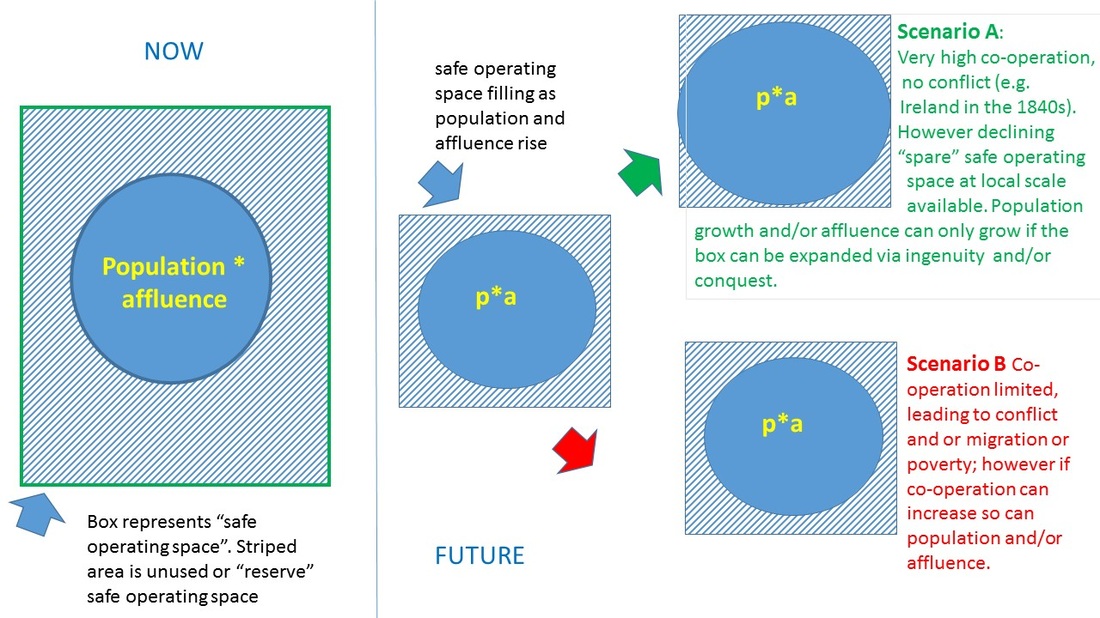

Abstract This paper presents an overview of the “Limits to Growth” debate, from Malthus to Planetary Boundaries and the Planetary Health Commission. It argues that a combination of vested interests, inequalities, and cognitive impediments disguise the critical proximity to limits. Cognitive factors include an increasingly urbanized population with declining exposure to nature, incompletely substituted by the rise of simulated and filmed reality. Following prominence in the 1960s and early 1970s, fears of Limits to Growth diminished as the oil price declined and as the Green Revolution greatly expanded agricultural productivity. While public health catastrophes have occurred which can be conceptualised as arising from the exceeding of local boundaries, including that of tolerance (e.g. the 1994 Rwandan genocide), these have mostly been considered temporary aberrations, of limited significance. Another example is the devastating Syrian civil war. However, rather than an outlier, this conflict can be analysed as an example of interacting eco-social causes, related to aspects of limits to growth, including from climate change and aquifer depletion. To view the “root causes” of the Syrian tragedy as overwhelmingly or even exclusively social leaves civilization vulnerable to many additional disasters, including in the Sahel, elsewhere in the Middle East, and perhaps, within decades, globally. An aspect of the Limits to Growth debate that was briefly prominent was “peak oil”. Fear of this has fallen with the oil price. But this does not mean that Limits to Growth are fanciful or will apply only in the far future, even if (which seems unlikely) the oil price remains low. The proximity of dangerous climate change is the starkest example of an imminent environmental limit; other examples include declining reserves of phosphorus and rare elements. Crucially, human responses have the capacity to accelerate or delay the consequences of these limits. Greater understanding of these issues is vital for enduring global population health. Keywords: Anthropocene, civilization collapse, climate change, conflict, environmental determinism, human carrying capacity Introduction On world refugee day, 2016, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees announced that at the close of 2015 there were over 65 million displaced people on the planet (the majority of whom afire children), an increase of over 50% from the end of 2011 [1]. This increase is neither random nor coincidental, but a foreseeable consequence of planetary scaled socio-ecological (or “eco-social”) factors. Unfolding for decades, these forces continue to evolve in broadly predictable ways. The growing number of refugees (11.7 million in 2015 from Syria alone, now 1 million from South Sudan) shows the failure of the current world political system and the wishful bias of many policy makers and academics. The global progress that was, until recently, widely predicted [2] may be unravelling [3]. There are a few prominent exceptions, most notably Paul and Anne Ehrlich [4,5], but most commentators still remain optimistic. The most recent median projection for the size of the global human population in 2100 is of over 11 billion people, approximately 3.5 billion more than today. Average life expectancy at birth in 2100 is forecast to have risen 13 years above its recent (2010-2015) level of 70 years [6]. The Sustainable Development Goals are similarly confident [7]. Instead, humanity needs to appraise its stocks and prospects, environmentally and socially. The threats to civilisation may be higher than most experts and governments acknowledge [3]. Emergence, environmental determinism, or “risk multiplication”? Instead of viewing the catastrophe in Syria [8] as either an aberration or random, it can be conceptualized as a “canary case” of emerging “regional overload” [9]. An increasing number of authors [10-14] have argued that climate change aggravated the Syrian drought, in turn worsening aquifer depletion, also contributed to by ongoing population growth [8]. All of these analysts are very clear that these environmental stressors do not act alone to cause conflict, but interact with an established, fluid milieu whose elements include inter-group rivalry, resentment, unfair governance, inequality and outside interference. Yet most political scientists reject the claim of a significant contribution from anthropogenic climate change to existing and future conflict [15]. Attempts to link ecological and social factors with conflict have even been denigrated as “environmental determinism” [16], a philosophy whose origins have been traced to Baron de Montesquieu in 1748 [17]. In this perspective, social and historical phenomena are allegedly “controlled” by environmental factors, with little if any appreciation of the wider social and political context within which conflict may emerge. However, evidence of the existence of simplistic cases of environmental determinism in the recent peer reviewed literature is easier to allege than to locate. Denial of an environmental contribution to conflict appears also to discount systemic, emergent theories of causation, where many factors coalesce, but where few are necessary or sufficient [18,19]. Additionally, “political” factors, identified by some as of greater importance than environmental determinants [16] are themselves often inextricably blended with ecological elements, such as long-standing grievances due to displacement from favoured, resource rich locations. An alternative way to conceptualize the influence of environmental change upon phenomena such as conflict, migration and famine is to consider factors such as drought as “risk multipliers” (or dice-loaders), rather than “event deciders”. Using this conceptualization, many phenomena are “eco-social” rather than purely social or ecological, a causal model that also implies that the solutions to many dilemmas (including conflicts) are neither exclusively social nor environmental. The high rate of human population growth in Syria (although declining, the total fertility rate before the war was still far above replacement) [8] played a role, not only by accelerating local resource depletion, including of groundwater, but by reducing the “demographic dividend”, a benefit which helps to promote economic and human development [20]. One harmful consequence of the high fertility rate in Syria was high youth unemployment, reported as 48% in 2011, at the onset of the war, a fivefold increase from 2000 [8]. In turn, large numbers of young, underemployed, unfulfilled men (sometimes called “youth bulges”) have been linked to violence [20]. Malthus, Limits to Growth and limits to transparency and compassion The intellectual underpinnings of the emerging global eco-social crisis include Thomas Robert Malthus, The Limits to Growth, Planetary Boundaries and the Planetary Health Commission. Malthus (1766-1834) is mainly remembered for his prediction that human population growth (unless slowed by means such as delayed marriage) would growth in food supply growth, leading to reductions in living standards and (eventually) human population size. But the most fundamental contribution of Malthus was the idea that individuals and species, including humans, compete for scarce resources. Undoubtedly ancient, this insight was so well popularised by Malthus and his supporters that the key developers of the theory of evolution, Darwin and Wallace, each acknowledged their debt to him [21]. Soon after Malthus’s death the Irish famine was interpreted as supporting his central thesis [22]. Critics of Malthus instead pointed to the primacy of social, political and economic factors, particularly inadequate relief from England. However, these elements can also be accommodated into a broad interpretation of Malthus’s central idea (see Figure 1), including a limited willingness to provide relief. The Irish famine emerged from multiple factors, two of which were high population growth and high population numbers [22]. In turn, these influenced other causal elements of the famine, such as reliance by the poor on an affordable but ultimately highly vulnerable potato monoculture.  During the Irish famine (1848-1852), population roughly halved, due to deaths from famine and diseases with large-scale migration. The proximal cause was the potato blight, but this was exacerbated by minimal famine relief. During the famine, grain continued to be exported from Ireland. This lack of relief by Britain or any other power does not negate Malthus’s central concept. The term “limits to growth” became popular following publication of the book of that name in 1972 [23]. Using a systems approach, it presented a computerized model of the interconnected [3] global eco-social system. This work concluded that environmental decline, combined with accelerating population growth and resource scarcity, had the capacity, without reform, to precipitate civilization collapse by 2100, rather than by 2000 as many of its critics erroneously claimed [24]. Initially regarded with esteem, including by US President Carter [25] the influence of the Limits to Growth waned, due to the rise of neoliberalism and the success of the Green Revolution [25]. This backlash was also associated with the “cornucopian” doctrines of social scientists such as Julian Simon, who argued for laissez faire population growth, claiming that additional people were the “ultimate resource”, and thus to be welcomed anywhere and any time [25-27]. An important aspect of limits to growth theory is the decline in energy return on energy investment (EROEI) [28]. Although wind and solar power are increasingly important, these technologies still have a low EROEI. The decline in easily recoverable oil helped stimulate the oilsands boom and fracking, but the ingenuity each exhibits has not solved fundamental problems such as leaking greenhouse gases, especially methane, associated with fracking [29]. The fall in the price of oil since its two crests in 2008 and 2010 has led some commentators to argue that “peak oil” concerns have been overstated. However, few experts argue that the current comparatively low oil price will persist for more than a few more years. But even if abundant fossil fuel reserves are discovered, their exploitation is limited by the imperative to slow carbon dioxide (CO2) accumulation [30]. The maximum tolerable level of greenhouse gases in the ocean and atmosphere, quickly approaching [31], constitutes another limit to growth. Other environmental limits include of crop yields [32], phosphate reserves (essential for agriculture) [33], rare earths, helium, and some metals [34]. Ecosystem change is also limited [35], as are innovations such as Moore’s Law [36]. There are also limits to manageable complexity [3,37], as well as to co-operation, compassion and aid. People are rarely transparent, especially in milieux in which others are perceived as deceptive. Relatedly, distrust of recipients limits generosity and assistance, and also means, in many cases, that human population size over extended periods is lower than possible were inter-group co-operation much higher (see figure 2).  Populations can be conceptualised as inhabiting a “safe operating space” (SOS) some of which is used (the blue circles) by an area proportional to population, affluence and technology, and an unoccupied area, a “reserve” safe operating space (SOS). In scenario A, there is very little reserve SOS, but little significant conflict, nor migration or premature death. In scenario B, there is a greater reserve of SOS, but total population*affluence is not maximised, due to distrust and conflict, such as in Syria or South Sudan. The 2007-10 drought in Syria reduced the area of the box, reducing the reserve SOS and increasing the risk of conflict. Humans evolved to co-operate in small groups, themselves in competition with similarly co-operating groups [38]. Although honesty within one’s close group may be rewarded, openness and trust of rival group members, especially if competing [39], is unlikely, and could even be hard-wired. Can humanity broaden its conception of self-interest to the entire species? If so, can humans preserve sufficient ecosystem services to guarantee safety?

Planetary Boundaries and Planetary Health The term “planetary boundaries” defines a “safe operating space” for humanity [40,41]. Like the Anthropocene and the Earth system, these terms recognise and reflect the global scale of human biosphere alteration [42]. Planetary boundaries are not located at postulated critical biophysical thresholds, but up-stream, providing a safety margin of uncertain size. The initial formulation of planetary boundaries included nine Earth system processes, each modified by human action. The processes which have led to the proximity to planetary boundaries have helped humanity to reach its current level of dominance, but these processes have now “overshot”. The passing of most planetary boundaries will not necessarily reveal new health risks, but if sufficient boundaries are exceeded profound effects to the Earth system will be triggered, with profound adverse flow-on effects to health and other aspects of human well-being [42]. In 2014 the Planetary Health Commission (supported by the Rockefeller Foundation and The Lancet) was established to explore the significance of these ideas to health [43]. The Commission sought also to investigate how global health has improved despite an eroding environmental foundations, deciding “the explanation is straightforward and sobering: we have been mortgaging the health of future generations to realise economic and development gains in the present”. Cognitive Factors and Inequality as Barriers to Sustainability Millennia ago, the reliance of all humans on the environment is likely to have been apparent from an early age, even though numerous past populations did great ecological harm, at least locally, as people transformed their surroundings for perceived human benefit [44,45]. It is plausible that this sense of human-nature connection began to decline as agriculture was increasingly adopted, accompanied by the rise of urbanization and industrialization. Today, more than half of the world’s almost 7.5 billion people are urbanized. For affluent and influential populations, food is available in abundance, yet an increasing number of such people have scarcely any personal experience of growing food. Many such populations are also likely to be personally insulated from the stress, harm and risk of high ambient temperatures and humidity, each likely to worsen significantly in many areas due to global warming [46,47]. The rise of simulated and filmed nature may also be contributing to an erosion of popular understanding of civilisation’s risk, disguising the extent of harm that has already accrued, and contributing to the extent of cognitive dissonance [48]. The phrase “the 1%” reflects the rise of inequality in the US and many other countries [49]. Excessive unfairness reduces resilience and increases the risk of collapse [3,50]. The most affluent people on Earth not only have the greatest privilege but the most political influence [51]. Many decision makers are likely to be disproportionately protected from other direct adverse effects of global environmental change, including extreme events such as flooding, but may be more vulnerable to highly indirect “tertiary” (systemically arising) effects of adverse eco-social change including conflict, mass migration and even terrorism [52,53]. Conclusion A distinguished and growing number of scientists, futurists and policy makers, including the governor of the Bank of England, have warned that current dominant practices will place civilization at risk, via pathways that include nuclear war [42]. A breakdown in global public health, leading to increased epidemics, on a background of deteriorating eco-social phenomena that damage health determinants is also a plausible scenario [54]. Today, humans prey on nature. Although Pinker and others argue that violence by humans against humans has declined [55], the violence of our species against nature is rising. This cannot continue. These challenges, created by our species, may still be soluble, but this will require far more honesty, courage, understanding, human resources and high level attention than has recently been made available. It also requires greater openness and sharing. Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Dr Kerryn Higgs for her helpful comments. References 1. UNHCR: Global Trends Report. Forced Displacement in 2015. UNHCR, (2016). 2. Johnson DG: Population, food, and knowledge. American Economic Review (2000) 90(1):1-14. * Exemplifies the optimistic "cornucucopian" position, arguing that ingenuity will indefinitely overcome resource scarcity. This paper, typical of this genre, ignores or disregards counter-examples, such as the Rwandan genocide of 1994. 3. Lechner S, Jacometti J, McBean G, Mitchison N: Resilience in a complex world – Avoiding cross-sector collapse. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction (2016) 19(84-91. ** excellent summary of interconnected risks, though rather optimistic from an ecological perspective; no discussion of conflict 4. Ehrlich PR, Ehrlich AH: Population, resources, and the faith-based economy: the situation in 2016. BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality (2016) 1(1):1-9. ** Characteristic of the minority perspective which argues that "business as usual" is perilous for human well-being. 5. Ehrlich PR, Ehrlich AH: Can a collapse of global civilization be avoided? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2013) 280(1754). 6. The 2015 Revision of World Population Prospects: (2015). http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/ March 10, 2016 7. Brown JH: The oxymoron of sustainable development. BioScience (2015) 65(10):1027-1029. 8. Taleb ZB, Bahelah R, Fouad FM, Coutts A, Wilcox M, Maziak W: Syria: health in a country undergoing tragic transition. International Journal of Public Health (2015) 60(1):63-72. 9. Butler CD: Planetary Overload and Limits to Growth and Health. Current Environmental Health Reports (in press). 10. Gleick P: Water, drought, climate change, and conflict in Syria. Weather, Climate, and Society (2014) 6(331–340. 11. Kelley CP, Mohtadi S, Cane MA, Seager R, Kushnir Y: Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA) (2015) 112(11):3241-3246. 12. Bowles DC, Butler CD, Morisetti N: Climate change, conflict, and health. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (2015) 108(10):390-395. 13. Werrell CE, Femia F, Sternberg T: Did we see it coming? State fragility, climate vulnerability, and the uprisings in Syria and Egypt. SAIS Rev (2015) 35(1):29-46. 14. Fröhlich CJ: Climate migrants as protestors? Dispelling misconceptions about global environmental change in pre-revolutionary Syria. Contemporary Levant (2016) 1(1):38-50. 15. Buhaug H, Nordkvelle J, Bernauer T, Böhmelt T, Brzoska M, Busby JW, Ciccone A, Fjelde H, Gartzke E, Gleditsch NP, Goldstone JA et al: One effect to rule them all? A comment on climate and conflict. Climatic Change (2014) 127(3-4):391-397. 16. Raleigh C, Linke A, O'Loughlin J: Extreme temperatures and violence. Nature Clim Change (2014) 4(2):76-77. * Asserts that a single paper linking conflict and climate change illustrates "environmental determinism", however without providing specific details. There are other papers in this genre, all of which make similar, poorly substantiated allegations 17. Coombes P, Barber K: Environmental determinism in Holocene research: causality or coincidence? Area (2005) 37(3):303-311. 18. Goldstein J: Emergence as a construct: history and issues. Emergence (1999) 1(1):49-72. 19. Goldstein J: Emergence: a construct amid a thicket of conceptual snares. Emergence (2000) 2(1):5-22. 20. De Souza R-M: Demographic resilience: linking population dynamics, the environment, and security. SAIS Review of International Affairs (2015) 35(1):17-25. 21. Young RM: Malthus and the evolutionists: the common context of biological and social theory. Past & Present (1969) 43(109-145 22. Gráda CÓ, O'Rourke KH: Migration as disaster relief: Lessons from the Great Irish Famine. European Review of Economic History (1997) 1(1):3-25. 23. Meadows D, Meadows D, Randers. J, Behrens III W: The Limits to Growth. Universe books, New York (1972). 24. Higgs K: Collision Course Endless Growth on a Finite Planet. MIT Press, Cambridge MA, USA (2014). ** Comprehensive recent review of the debate concerning Limits to Growth 25. Butler CD, Higgs K: Health, human population growth and the decline of nature In: The Sage Handbook of Nature. Marsden T (Ed) (in press). 26. Myers N, Simon JL: Scarcity or abundance? A debate on the environment. WH Norton, New York (1994). 27. Butler CD: Globalisation, population, ecology and conflict. Health Promotion Journal of Australia (2007) 18(2):87-91. 28. Hall CAS, Lambert JG, Balogh SB: EROI of different fuels and the implications for society. Energy Policy (2014) 64(141-152. 29. Schneising O, Burrows JP, Dickerson RR, Buchwitz M, Reuter M, Bovensmann H: Remote sensing of fugitive methane emissions from oil and gas production in North American tight geologic formations. Earth's Future (2014) 2(10):548-558. 30. McGlade C, Ekins P: Un-burnable oil: An examination of oil resource utilisation in a decarbonised energy system. Energy Policy (2014) 64(102-112. 31. Anderson K: Talks in the city of light generate more heat. Nature (2015) 528(437. ** convincing and disturbing critique, arguing that much of the optimism the 21st UN Conference of the Parties on climate change is based on wishful thinking. 32. Grassini P, Eskridge KM, Cassman KG: Distinguishing between yield advances and yield plateaus in historical crop production trends. Nature Communication (2013) 4( 33. Cordell D, White S: Tracking phosphorus security: indicators of phosphorus vulnerability in the global food system. Food Security (2015) 7(2):337-350. 34. Klare MT: The Race for What's Left: The Global Scramble for the World's Last Resources (2012). 35. Dirzo R, Young HS, Galetti M, Ceballos G, Isaac NJB, Collen B: Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science (2014) 345(6195):401-406. 36. I.L.Markov: Limits on fundamental limits to computation. Nature (2014) 512(147–154 37. Taylor TG, Tainter JA: The nexus of population, energy, innovation, and complexity. American Journal of Economics and Sociology (2016) 75(4):1005-1043. 38. Nekola JC, Allen CD, Brown JH, Burger JR, Davidson AD, Fristoe TS, Hamilton MJ, Hammond ST, Kodric-Brown A, Mercado-Silva N, Okie JG: The Malthusian–Darwinian dynamic and the trajectory of civilization. Trends in Ecology & Evolution (2013) 28(3):127-130. * Calls for rapid cultural evolution if civilisation is to endure. Useful review of debate between Cornucopians and Malthusians 39. Schubert M, Lambsdorff JG: Negative reciprocity in an environment of violent conflict: experimental evidence from the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Journal of Conflict Resolution (2014) 58(4):539-563 40. Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson Å, F. Stuart Chapin I, Lambin EF, Lenton TM, Scheffer M, Folke C, Schellnhuber HJ, Nykvist B et al: A safe operating space for humanity. Nature (2009) 461(472-475. 41. Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson Å, F. Stuart Chapin I, Lambin EF, Lenton TM, Scheffer M, Folke C, Schellnhuber HJ, Nykvist B et al: Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society (2009) 14(2). 42. Butler CD: Sounding the alarm: health in the Anthropocene. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (2016) 13( 665; doi:610.3390/ijerph13070665. 43. Whitmee S, Haines A, Beyrer C, Boltz F, Capon AG, de Souza Dias BF, Ezeh A, Frumkin H, Gong P, Head P, Horton R et al: Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. The Lancet (2015) 386(1973–2028. * Hints that civilisation collapse is plausible; of significance as published in a high-ranking medical journal 44. Raudsepp-Hearne C, Peterson GD, Tengö M, Bennett EM, Holland T, Benessaiah K, MacDonald GK, Pfeifer L: Untangling the environmentalist's paradox: Why is human well-being increasing as ecosystem services degrade? BioScience (2010) 60(8):576-589. 45. Pitulko VV, Tikhonov AN, Pavlova EY, Nikolskiy PA, Kuper KE, Polozov RN: Early human presence in the Arctic: Evidence from 45,000-year-old mammoth remains. Science (2016) 351(6270):260-263. 46. Lelieveld J, Proestos Y, Hadjinicolaou P, Tanarhte M, Tyrlis E, Zittis G: Strongly increasing heat extremes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in the 21st century. Climatic Change (2016) 1-16 DOI 10.1007/s10584-10016-11665-10586. 47. Pal JS, Eltahir EAB: Future temperature in Southwest Asia projected to exceed a threshold for human adaptability. Nature Climate Change (2016) 6(197–200. 48. Rees W: What’s blocking sustainability? Human nature, cognition and denial. Sustainability: Science Practice and Policy (2010) 6(2):13-25. ** “Ours is allegedly a science-based culture. For decades, our best science has suggested that staying on our present growth-based path to global development implies catastrophe for billions of people and undermines the possibility of maintaining a complex global civilization. Yet there is scant evidence that national governments, the United Nations, or other official international organizations have begun seriously to contemplate the implications for humanity of the scientists’ warnings, let alone articulate the kind of policy responses the science evokes. The modern world remains mired in a swamp of cognitive dissonance and collective denial seemingly dedicated to maintaining the status quo. We appear, in philosopher Martin Heidegger’s words, to be “in flight from thinking.” 49. Oxfam: Having It All and Wanting More. OxFam, (2015). 50. Motesharrei S, Rivas J, Kalnay E: Human and nature dynamics (HANDY): Modeling inequality and use of resources in the collapse or sustainability of societies. Ecological Economics (2014) 101(90-102. 51. Butler CD: Inequality, global change and the sustainability of civilisation. Global Change and Human Health (2000) 1(2):156-172. 52. Butler CD, Harley D: Primary, secondary and tertiary effects of the eco-climate crisis: the medical response. Postgraduate Medical Journal (2010) 86(230-234. 53. Butler CD: Climate change and global health: a new conceptual framework - Mini Review. CAB Reviews (2014) 9(027. 54. Butler CD: Infectious disease emergence and global change: thinking systemically in a shrinking world. Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2012) 1(5. 55. Pinker S: Decline of violence: Taming the devil within us. Nature (2011) 478(309-311. |

AuthorColin Butler

|